The Tall Grass Dyepot Project

By Barbara Korbel

Human history is written on a foundation of adventure and discovery. Early explorers crossed the oceans with only an inkling of what they might find. Embracing the unknown, they began their journeys directionally empty-handed, and returned with documentation of their travels: maps, specimens and stories of personal encounters with the new.

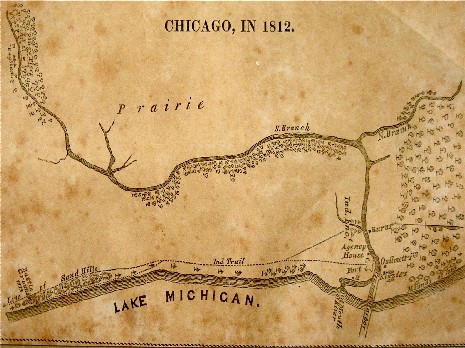

These days we can't imagine life without direction. We rely on tracking advice from a variety of sources—maps, computer searches, and, most recently, global positioning systems—all of which keep us from getting lost. And yet, even with all of our resources, we occasionally still lose our way. Such was my experience with a map drawn in 1812, twenty years before the city of Chicago was founded.

Courtesy The Newberry Library, Chicago. Call # Vault Ruggles

It is spare in detail, topographically recording only the shoreline of the lake, the river and its branches, the forests to the north and the prairie—the flat open landscape that defines the Midwest. Links to the geography that challenged our ancestors have not yet been broken, and for those of us born here, the prairie continues to capture our imaginations in countless ways. Almost two hundred years after this map was made, it inspired a long-term project called the Tall Grass Dyepot, a series of chapbooks that documents my explorations of native natural dyes.

The project began as an investigation of the plants that make up the grassland ecosystem. With a rudimentary knowledge of natural dyes, I began collecting and processing native plants simply to see what colors they would give. The more I learned about the plants that evolved to survive the extreme climate changes and uncertainties of the prairie environment, the more quickly the project took on a life of its own. Tall Grass Dyepot continues to explore natural dyes of the Midwest, but also includes images and references to the geographic and human history of the prairie and the transitional forests that border it.

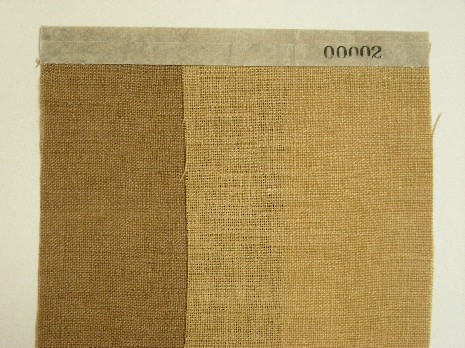

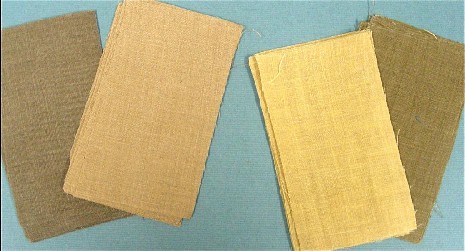

The first book was completed in May 2011. It documents the earliest steps taken on this journey. Those steps took me only as far as my front door, where maple, ash and elm leaves had stained the sidewalk after days of constant rain. I collected the leaves, made a stock solution and dyed my first pieces of linen. The resulting ochre cloth was divided, and the second half soaked in an iron mordant to "sadden" the color.

| Leaves from my front yard | Samples dyed with the leaves |

|

|

| Photograph Copyright by Barbara Korbel | Photograph Copyright by Barbara Korbel |

| Tall Grass Dyepot book | ||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Barbara Korbel |

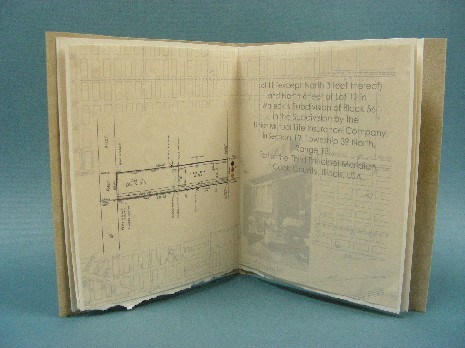

That book became the prototype upon which all the others in the series will be based. It is printed on handmade linen and abaca paper using an inkjet printer and is bound into a linen paper cover. The book is sewn and assembled by hand and produced in a limited edition of eight.

A map that refers to the location of the plant material that was collected, along with references such as plats, photographs, and other visual imagery connecting the reader to the place, spans an opening. Those site-specific references are also found in a small poem, although other narrative forms chronicling the history of a site may be used in future books. A specimen from the plant, samples of the dyed cloth, the recipe for extracting the dye and images of the plant are also part of the text.

From the beginning of May, when plant life returned to the Midwest, until the time of this writing, I spent much of my time lost outdoors—photographing, collecting, processing plant matter and dyeing fabric. The second book took me to the shoreline of Lake Michigan, where the transition from oak forest to prairie dominates the landscape. Fallen leaves and acorns from bur oak, Quercus macrocarpa, gave two very different yellows that were also mordanted with iron in subsequent baths. Drought and fire-resistant, the bur oak forms a natural fire break in the grassland ecosystem, making it an obvious choice when investigating the resilience of the prairie and the people who settled it.

The Chicago portage used by Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet to access the Mississippi via Lake Michigan is the subject of the third book in the series. A plant that grows in abundance at the site of the portage is pokeweed, Phytolacca americana, which gives a reddish pink dye. Waiting for the berries to ripen, I am reminded that the most satisfying experiences in nature require patience and cannot be rushed.

| The Chicago Portage | Pokeweed |

|

|

| Photograph Courtesy Rickdrew via WikiMedia Commons | Photograph Copyright by Barbara Korbel |

The tall grass prairie is defined primarily by its diversity of plant life. It is a place of overwhelming possibility for a dyer, and so, I continue to wander the fields, following cycles dictated by the natural world. The Tall Grass Dyepot is ultimately a project about process and the joy of discovery. Even when the result is not as dramatic as anticipated—or as hoped for—finding a plant that speaks for a place, and working with it to release whatever color is available, has, so far, been enough.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal