The School of Naval Medicine

By Kathy Hattori

The International Symposium and Exhibition on Natural Dyes (ISEND) was held in La Rochelle, France in April 2011. During the week- long conference we heard from over 80 presenters about natural dyes from all over the world speaking on subjects as diverse as nano-pigments and polylactic acid composites, as well as reports from NGOs, cultural preservation projects, designers and artists. Each day was filled with fascinating presentations, demonstrations and lively discussions about issues, trends, opportunities and new research on natural dyes.

Mid-week, we were treated to a morning of excursions featuring a choice of bus trips to various venues. We could go to the seashore to experience purple mollusk dyeing and oyster farming, visit a commercial grower of dye plants and a cattle ranch in the countryside, take a specialized docent-led tour of the Museum of Natural History and the old town of La Rochelle or go to Rochefort to visit the Regional Centre for Innovation and Technological Transfer in Horticulture (CRITT) natural dye extraction and application laboratory, a revitalized dye garden and the Naval Academy of Medicine. I chose to go to CRITT and was curious to see the dye garden, but what did not resonate with me at first was the visit to the School of Naval Medicine which was included in the tour. It sounded dry and stuffy and I quickly dismissed it as a quick side visit to an old French building with an indifferent tour guide droning on about some mundane historical events. Was I ever mistaken: the School of Naval Medicine is the world's oldest naval medical school and houses an extensive collection of historical plant specimens, including dye plants and medicinal botanicals. It proved to be a fascinating place.

The School of Naval Medicine Museum is housed in a renovated wing of the former School of Medicine, which was established in 1722. The French Navy donated the collection and the property to create a national museum, which opened to the public in 1998.

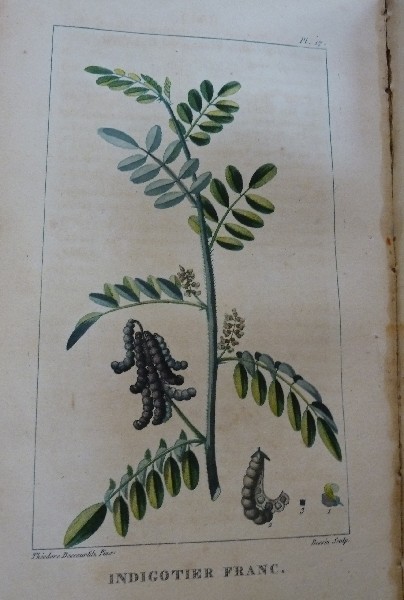

| Botanical illustration of Indigo | ||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Kathy Hattori |

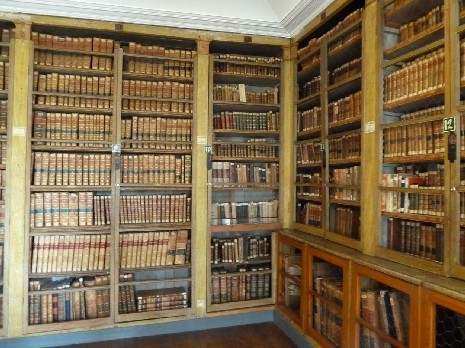

When we arrived at the Museum we were ushered into the main library, which contains 25,000 leather bound volumes on all aspects of science and medicine neatly shelved on bookcases covered with wire doors in the style of Louis XVI. The books are very old (many were printed before 1500) and represent the broad spectrum of subjects that doctors and surgeons were required to study; not only did they need to know anatomy, surgical medicine and diseases, but they also studied botany, as at that time, pharmaceuticals were derived almost exclusively from plants. The library staff selected a number of antique volumes that included engravings of dye plants and we were able to examine them closely.

|

Library stacks at the School of Naval Medicine |

Exhibit room at the School of Naval Medicine |

|

|

| Photograph Copyright by Kathy Hattori | Photograph Copyright by Kathy Hattori |

The group then filed up the spiral staircase to the uppermost floor of the Museum. The top floor houses the anatomical, zoological, botanical and ethnological collections. What a cabinet of wonders! During its heyday, the School had been a center for knowledge and attracted not only medical researchers, but also other scientists and intellectuals. The wide ranging subjects of the collection bear witness to the enormous body of knowledge assembled by the School.

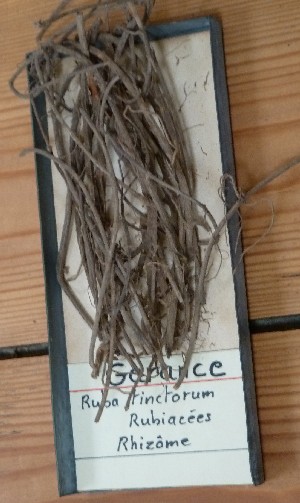

The collection rooms were large and airy and the sky lit rooms were dominated by huge glass-fronted cases full of treasures. Everywhere you looked there was something interesting that made you want to press your nose up against the glass and really look at. One room held a horse skeleton, in another room was a long wooden dugout canoe and a white marble bust of a French noble or scientist. Floor to ceiling cases displayed enormous calipers and rows of skulls, skeletons and nervous system maps. Other cases held warrior axes, surgical tools, and huge pine cones in handblown bottles. Everything was meticulously categorized and labeled in French copperplate cursive. Many of the cabinets had small metal trays filled with botanical specimens, bits of bone and horn, vials of mysterious fluids and gnarled roots, presumably used for making medicine. The staff had laid out a display of dye plants on one of the work tables and we were able to examine old specimens of madder root, cochineal insects, logwood and gall nuts.

| Samples of natural dye materials from the Museum's collection | Sample of madder root |

|

|

| Photograph Copyright by Kathy Hattori | Photograph Copyright by Kathy Hattori |

We only had a few minutes to take in centuries worth of collecting and I lingered over the natural dye materials, thinking back to the time when all of this was so new and experiments were being conducted on the properties of natural dyes for textile and medicinal uses. Now most of us use natural dyes strictly for coloring cloth, but there was a time when the search for medicines and the search for color were much more closely interdependent and discoveries in one area led to advances in another. The short visit to the School of Naval Medicine Museum brought a deeper appreciation to the disciplines that led to the development of natural dyes and color in 18th century France and the diligent preservation that allowed me to enjoy this collection in a very unique setting.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal