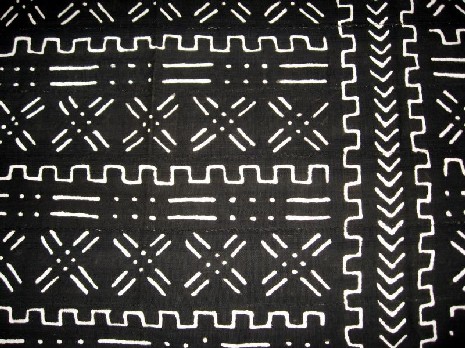

Bogolan Fini from Mali, Africa /

Modified Mud Cloth from Ohio, US

By Judy Dominic

I've been a "down to earth" sort of person all my life, so when the idea of dyeing with mud and dirt came across my horizon, it seemed like the perfect thing to do. Here was a surface design technique that seemed to require nothing more than playing in the dirt!

Mud cloth, or bogolan fini* as it is called in Mali, Africa, consists of white designs, often geometric, on a black background. In use for centuries, the technique of decorating cloth with mud is handed down from mother to daughter, and has its origins in the legend of a hunter accidentally falling into river mud. While natural dyes from trees and plants were already in use, this fortuitous "accident" demonstrated the powerful effects of the almost black mud on previously dyed cloth.

The bogolan process is an interesting one which can't be duplicated outside of Mali. It begins with a family growing the cotton which women spin into thread, and give to men to weave into cloth. Women then sew and dye the strip-woven cloth. The sewn-strip cloth is often left as a simple straight piece of fabric and used as a wrap skirt for a wedding or other rite of passage. The cloth may also be used as blanket for a newborn, a hunter's shirt, or in a funeral.

While the cotton is being grown, spun and woven, mud from the Niger River is collected and covered with water in a clay pot for a year before it is ready to use. Leaves and bark from trees and bushes (wolo, n'galama, n'peku and indigo) are gathered and soaked or cooked in water to form natural dye solutions of yellows, russet and blue.

| Lengths of cotton dyed in local natural dyes showing the range of colors available in Mali | ||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Judy Dominic |

The cloth to be mud dyed is dipped in one of the natural dyes and spread in the sun to dry. Three dippings and dryings (with the darker sun side up each time) prepare the cloth surface to take the mud color easily—basically the cotton fabric has been mordanted with tannin at this stage, although Malians do not refer to it as such. The cloth is then spread out, ready for the mud. Traditionally, bogolan artists have used large calabashes (gourds) as their working surface; contemporary artists use tables and floors for their work surfaces.

The artist uses a sharpened stick, dipping it into a pot of mud and then drawing the outline of the design she has in mind. Each detail of the overall design is symbolic of something from the village, people or ancestry important to the person for whom the cloth is being made. Placement of the individual designs is also significant in the overall "telling of the story" through the symbols. Once all the outlines are drawn on the cloth, the artist then fills in the background with the mud.

As the mud dries, it turns a lighter grey color, while the tannin color darkens in the sun. The dried mud is rinsed off, leaving a deep brown/black color. The cloth is then re-dipped in one of the natural dyes and re-dipped in the mud one or more times, depending on how dark the desired background. After rinsing off the final layer of mud, the design areas not mudded are treated with a caustic solution made from wood ash and mixed with cooked, mashed ground nuts or shea butter to give them some "body" (sort of like our bleach gel pens). This bleaches out the dye color and brings the un-mudded portions of the cloth back to the original white. With intricate designs, this entire process can take up to four or more weeks. The chemistry between the natural dye and the iron-rich river mud is magic—the color is immediate and intensely dark. The only reason to dry the cloth after applying the mud appears to be to keep the background mud/color from spreading into the design areas.

This is how bogolan fini is done in Mali. Some minor process variations exist between villages and individual artists, but do not change the outcome of the technique. Contemporary bogolan fini artists, including many men, are changing some of the methods, using stencils to shorten the production time or adding a broader range of natural dye colors left on the cloth. Nonetheless, the basics remain the same: dye the cloth, mud the background and/or any black areas of the design, rinse, repeat, and bleach. In this age of instant gratification, bogolan fini does not even come close!

In trying to duplicate those lovely and luscious black and white cloths in my studio, I found there were too many variables beyond my control. These included soil content, water content, properties of the locally grown cotton, with its thicker and more absorbent handspun threads, and natural dyes that are not available outside of Africa. In addition, there is the tropical sun and heat which certainly does not characterize the climate of southwest Ohio. Although not a scientist, I did try to come as close to the process as possible at first, using a purchased powdered tannic acid, boiled tannin from oak bark and strong tea water. The boiled tannin provided the result closest to the Malian process, but was still not very dark. Although tannins have not worked for me, I have discovered several ways to obtain lovely color from mud by taking advantage of the wide variety of dirt we have around us and the pigments they offer.

Solution #1: Soy Milk

A lecture by noted color expert Michele Wipplinger (www.earthues.com) during Convergence 1998 Atlanta, brought up the use of soy milk. There is an enzyme in the protein of soy, similar to that of blood, which likes to bind. (Ever wonder why the bibs from babies drinking soy formula were always dirty looking?) With time, soy can bind color to cloth extremely well. Various cultures have used soy milk in the dyeing. Michele spoke of the dyers in the South American Andes, and Japanese dyeing expert John Marshall (www.johnmarshall.to) follows the centuries-old method of using soy on silk when doing katazome. My initial soy milk/mud experiment resulted in a definite improvement over the use of tannin.

I am not as meticulous in my work as either Michele or John. Therefore, when I use a straight soy milk solution, it tends to bind EVERYTHING to the cloth, even the debris in the dirt if I haven't cleaned it well. When using soy at full strength, the pigment/color seems to sit on the top of the cloth, rather than saturate the fibers. Using equal parts soy milk and water, and then blending that solution with the dirt to make a thinner mixture works best for me. Dyeing thick cottons rather than sheer silks was just one of the variables to consider in adjusting techniques to my work.

The mud/soy/water mixture is painted on the cloth, allowed to dry, and then stored out of sight so I'm not tempted to rinse it off too soon. Once the mud is mixed with soy, I keep it refrigerated and use it before it goes "off" and starts smelling. Both home-made and store-bought soy milk work for me.

As mentioned earlier, soy likes time. Letting the cloth dry and then putting it away for a minimum of two weeks will give those enzymes time to work. Six months to a year or more is even better. Once rinsed, the cloth should be treated like a fine piece of clothing: dry clean or handwash in cold water, with mild soap and light agitation. It can also be re-mudded at any point after rinsing, in order to make the colors darker.

When I have the luxury of letting the cloth sit, I prefer the soy method. When teaching mudcloth workshops, suggesting to students to let their cloth sit for a long period of time does not always meet with enthusiasm. This prompted me to keep experimenting.

Solution #2: Calcium Carbonate

In one of my other fiber lives, I make paper from plant materials. In coloring pulp (plant fibers) with pigment (dirt!), papermakers use what is referred to as Retention Agent—a crystalline substance that when mixed with water produces a slimy solution. This substance is basically calcium carbonate, which is attracted to pigment particles and will bind tightly with them. If plant fibers such as cotton, linen, ramie, hemp, etc. happen to get between the calcium carbonate and the pigment, the pigment is held fast to the fibers—immediately. [Note: when mixed directly with dirt or mud, the calcium carbonate solution becomes crystal clear with balls of dirt clumped on the bottom of the container—pretty dramatic.] Using calcium carbonate to keep mud colors on cloth does have a drawback as it will grab hold of EVERY pigment particle it can, even when being rinsed off. The immediacy of its holding power often outshines any unplanned graying of white areas.

I have used the calcium carbonate in several ways: dipping the cloth prior to mudding, painting calcium carbonate on the back of the cloth directly behind the mudded designs, and painting calcium carbonate on top of the mudded designs on the front of the cloth. The first two methods retain more color, but all three methods hold more color right away than soy milk. On the other hand, when given a fair amount of time to work, soy milk edges out calcium carbonate in terms of holding color.

Most of my mud cloth work has centered on using plant fibers (cellulose), in recognition of the bogolan fini tradition. I have found that both the soy and the calcium carbonate methods work equally well on silks (protein fiber).

| Cotton/linen skirt dyed with New Zealand dirts and soy milk by the author | ||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Cindy Wagner, Wagner Photographics |

I thoroughly admire the traditional methods of creating mud cloth, knowing that I will never be able to accomplish the traditional process outside of Africa. It is interesting, however, that with a palette of lovely earth colors, including a variety of ochres, which they use for mudding their adobe-like buildings, bogolan fini utilizes only the Niger River black. I am happy to confidently use all the gifts of color from the earth wherever I happen to be.

* Bogo = mud, lan = result of, fini = cloth

References:

Imperato, PJ & Shamir, M., 1970. Bokolanfini—Mud Cloth of the Bamana of Mali. African Arts 3(4):32-42.

Toerien, Elsje S., 2003. Mud cloth from Mali: its making and use. http://ajol.info/index.php/jfecs/article/viewFile/52840/41441.

Rovine, Victoria, 2001. Bogolan: Shaping Culture through Cloth in Contemporary Mali.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal