Japanese Kyoukechi Dyeing

By John Marshall

The Japanese people have a long and glorious history of interest in textiles. Over the centuries many methods have been developed to feed this hunger. One such technique called kyoukechi was originally brought to Japan from China. Domestic production reached its peak during the Nara Period (710-794) and then gradually died out. Interest was later reborn during the middle of the 18th century in the form of what is called itajime), or board clamping.

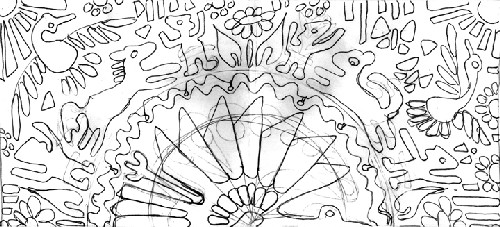

In anticipation of an exhibit held in conjunction with the recent Textile Society of America gathering, I was asked to prepare a few kyoukechi pieces. I sketched a design, Dance of Life, and carved it in mirror image on two identical boards. In this case, the wood was hand-hewn, old-growth California redwood dating back to the 1880s.

To create an image, I cut deep channels into the wood, producing moats into which the dye flows. The high areas act as dams, restricting the flow of color. Holes are bored through the entire thickness of the board to allow dye to flow into difficult-to-reach or restricted areas.

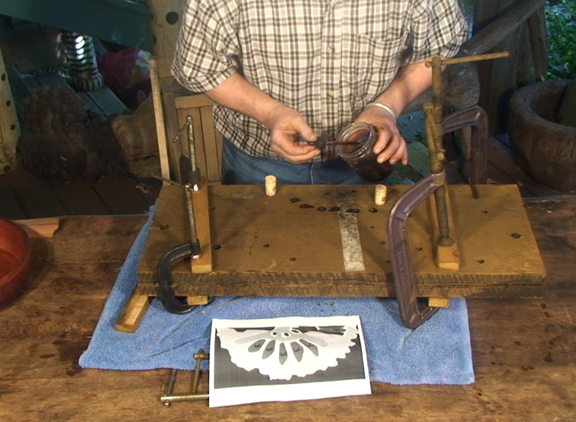

I carefully measured the dimensions of the design repeat and fit the folded cloth to size. This step is crucial for achieving accurate images. Gently laying the top board in position I sandwiched the fabric between the twin images. Care must be taken to match the carved areas precisely. The raised, matched areas of the block pinch the cloth, preventing dye from wicking. Toward this end, the boards must be clamped to insure good, even pressure.

The local biodynamic farm saves onionskins for me in large quantities. I added the dried onions skins to boiling water to brew a solution of yellow dye and then tossed in some baked alum as the mordant. The clamped cloth was placed into the vat and steeped until a sufficient depth of color was achieved. This will became the base coat of color for the entire pattern. The holes and moats allow the dye to penetrate to the centermost areas of the pattern. Some of the raised areas act as dams, fully enclosing areas of color. The diagram indicates the location of specific dams, into which isolated color will be added.

Lac and Indian sumac were prepared using a tin mordant. The hot liquid is then added to the contained areas with an eyedropper. Notice how the holes on the bottom side have been plugged with cork. The corresponding holes on the top side will also be plugged before the boards are dipped into the vat.

I slowly lowered the clamped boards into the dye vat, and once the boards were submerged, they were held under the surface of the liquid to allow the air to be displaced by the indigo. Slowly the boards are lifted out of the vat, allowing the excess dye to drain from the boards. This helps pull in air through the holes to allow the innermost indigo to oxidize. This process of dipping and pulling out to oxidize is repeated until the desired shade of indigo is achieved.

The cork stoppers prevent the indigo from affecting the color of the red added earlier. The uncorked holes allow the dye to penetrate freely. Holes may be corked and uncorked at will to achieve a variety of colors and shades.

The indigo-dyed fabric is allowed to sit overnight to insure complete oxidation. The clamps are removed and the boards separated to reveal the completed design. Notice how well the multiple layers of cloth have preserved the pattern of the boards.

The dyed fabric is peeled from the boards

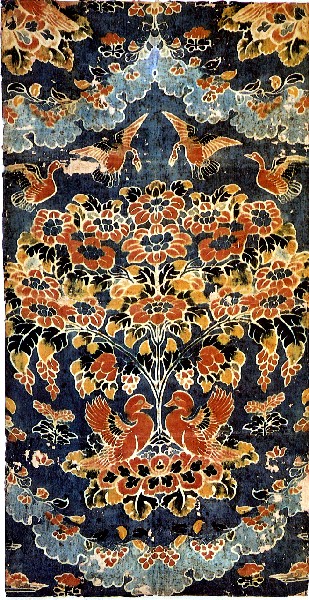

This is an example of a Nara Period kyoukechi textile, from the collection of the Shosoin, in Nara. This type of multiple-color panel is called tashoku kyoukechi, or compound-color kyoukechi. It was considered a very luxurious form of dyeing, in stark contrast to the mostly solid colors seen at that time. The commonly used dyes were ai (indigo, Polygonum tinctorium) for blues, kariyasu (Miscanthus tinctorus) for yellows, akane (madder, Rubia cordifolia) for reds, which gave the artist a very broad range of color combinations with which to work.

on an "ashiginu" weave (leno).

|

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal