Blue

The Textile Museum

Washington, DC

BLUE, on view at The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. April 4 through September 18, 2008, celebrates the creative vision of contemporary textile artists working with natural indigo dyes and explores the history and significance of blue textiles across time and place. This exhibition is a follow-up to the 2007 Textile Museum exhibition RED.

Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

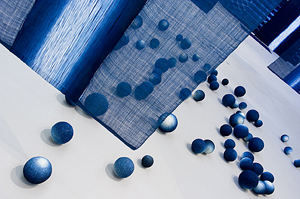

Hiroyuki Shindo, Shindigo Space 07, 2006. 'Shindigo shibori'-dyed cotton and hemp and Shindigo balls (polystyrene wrapped with hemp and dip-dyed). Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Joel Chester Fildes. |

BLUE features dynamic installations by contemporary artists working in Japan, South America and the United States—as well as 30 historical textiles drawn from The Textile Museum's renowned collection and originally created in the Americas, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Complementing the exhibition is a film by Mary Lance, a work-in-progress of the upcoming documentary Blue Alchemy: Stories of Indigo. BLUE is co-curated by Lee Talbot, Assistant Curator for Eastern Hemisphere Collections, and Mattiebelle S. Gittinger, Research Associate for Southeast Asian Textiles.

Blue: A Color both Timely and Timeless

BLUE is one manifestation of a renewed focus on the color blue. From designer fashions and furnishings to stylish automobiles and advertising, blue reigns as 2008's most popular color. Cathy Horyn of The New York Times recently reported, "There has indeed been a surge of blue on the runways in the last year... And JWT, the advertising and marketing company, just named blue as one of the top 10 trends for 2008, saying that 'blue is the new green,' particularly as it denotes ecological concerns."

Despite its timely popularity, the use of blue dyes dates back four millennia. Concurrent centers in such diverse locations as Egypt, South Asia and Peru independently developed ways to use blue dyes several thousand years ago. Subsequently the skills spread to adjacent regions and eventually to most of the world. Benign climate conditions favored the growth of indigo-bearing plants—of which there are several hundred varieties. Where climate did not cooperate, trade provided the dyestuffs, and indigo became a central commodity in international commerce and colonial economies. Indigo-dyed clothing came to be worn by all social classes in cultures across the globe.

Fireman's coat, Japan, 19th century. The Textile Museum 1983.65.1. Ruth Lincoln Fisher Memorial Fund. Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

Navaho Chief's Blanket, Phase 1, ca. 1850. The Textile Museum 1976.30.3. Gift of Col. F.M. Johnson, Jr. Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

Ecological and Aesthetic Concerns Spur Artists' Return to Natural Indigo

While blue dyes can be derived from Murex snails, logwood and other natural substances, for millennia indigo remained the most important source of the color blue in the manmade environment worldwide. Although a synthetic version superseded natural indigo throughout much of the 20th century, even earning its originator a Nobel prize, the return of natural indigo dyes in recent years represents artists' search for natural, ecologically-friendly materials that speak to their own experiences.

Hiroyuki Shindo, whose work Shindigo Space 07 is on view in BLUE, is a key figure in the revival and transformation of natural indigo dyeing in Japan. Shindo processes his own indigo to produce innovatively patterned textiles. As a young man, he was enraptured by the colors achieved with natural indigo, but saddened by the dramatic decline in indigo farming, processing and dyeing that accompanied Japan's modernization. Through his career he has helped to revitalize and develop this ancient craft.

Hiroyuki Shindo, Shindigo Space 07 (detail), 2006. 'Shindigo shibori'-dyed cotton and hemp and Shindigo balls (polystyrene wrapped with hemp and dip-dyed).Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Joel Chester Fildes.

Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

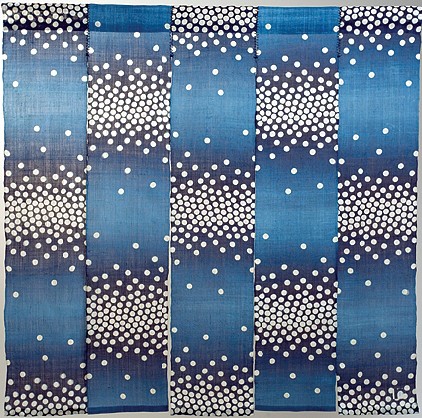

A second Japanese artist represented in BLUE, Shihoko Fukumoto, is primarily concerned with space, and for her, ai, natural Japanese indigo dye, is more than just a shade of blue—it is the color of space. Combining the demanding traditional Japanese crafts of indigo dyeing, or shibori, and tonal gradation dyeing, bokashi, Fukumoto creates works of luminous, transcendent beauty.

Shihoko Fukumoto, Between East and West, 2003. Shibori stitch and pleat resist and indigo-dyed cotton and velvet. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

||

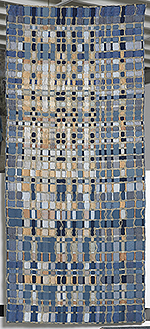

Artists Maria Eugenia Davila and Eduardo Portillo, who also have artwork on view in BLUE, are spearheading the techniques of rearing silk worms, weaving with locally sourced fibers and dyeing with natural dyes in Venezuela. They were inspired to work with natural indigo by visits to Orinoco and the Amazon. The artists spent several years in China and India studying sericulture, or silk farming, and since then their research has taken them worldwide. In Venezuela they have established the entire process of silk manufacture: they grow mulberry trees on the slopes of the Andes, rear silkworms, obtain the threads, color them with natural dyes, and design and weave innovative textiles.

Maria Eugenia Davila and Eduardo Portillo, Guardian, 2006. Silk, Moriche palm fibers and wool from the Andean mountains. Dyed with indigo, eucalyptus and cochineal and handwoven in triple weave. Collection of The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK. Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

Kain panjang (long cloth, hip wrapper) detail, Indonesia, Yogyakarta (in the style of Ceribon), Chinese-Indonesian, 20th century. Commercial cotton, resist patterning. The Textile Museum 1998.11.16. Gift of Beverly Deffef Labin Collection. Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

|

An American artist represented in BLUE, Rowland Ricketts, began working with indigo during a two-year apprenticeship in Tokushima, Japan. He spent one year learning to farm and process indigo plants and a second year studying the traditional wood-ash lye, natural fermentation indigo vat, and traditional shibori techniques. After his apprenticeship, Rowland established a studio and farm with his wife Chinami, a kasuri weaver. Together they farmed and hand-processed the indigo that they used in their work. Rowland and Chinami returned to the United States in 2003.

|

Rowland Ricketts, Untitled Noren Partition. Indigo dyed hemp, stencil paste resist. Courtesy of the artist. |

Photograph Courtesy The Textile Museum |

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal