A History of Duk

Facial tattooing with indigo dye of the Karbi women

of Northeast India

By Robindra Teron and SK Borthakur

The Karbi tribe and their herbal dyes

The Karbis are one the major tribes in Northeastern region of India, inhabiting mainly the states of Assam, Arunachal and Meghalaya and also the Chittagong Hill Tract in Bangladesh. Herbal dyes occupy a prominent place in the socio-religious life of the Karbis. Traditionally, a characteristic feature of a Karbi woman was her facial tattoo, dyed with indigo from the forehead down to the chin (Figure 1). Locally referred as duk in Karbi dialect, the tattoo was a symbol of culture, purity and status in the society.

Duk was an element of great cultural significance among the Karbis. Although tattooing is also practiced among many other ethnic groups of Northeast India, the Karbis' concept and practice of duk is unique and upholds traditional views of the dignity of women in particular and cultural identity of the Karbis in general. In the present time however, the practice duk is declining rapidly. Modern Karbi girls consider duk as being too old fashioned and think that it does not add beauty to the recipient, as it was considered in earlier days. Today, one can hardly find experts duk dyers. Duk as of now appears to be becoming a "dying art" and the associated traditional knowledge is likely to disappear from the community in the near future.

Ethnically, Karbis are Mongoloids and speak a dialect belonging to Tibeto-Burmese, particularly the Kuki-Chin subgroup of languages (Phangcho, 2001). They practice a patriarchal system of family; marriage is based on strict clan exogamy (one must marry someone from outside their own clan) and violation of this social rule is considered a serious crime which can lead to excommunication. Karbis are mainly agriculturists—jhum (shifting cultivation) is the main mode of agriculture in the hills. Rice is the staple food and locally prepared rice beer is a common drink of the people.

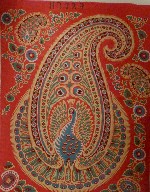

The Karbis use of natural dyes, their knowledge about dyestuffs and their techniques of dyeing textiles, crafts and tattoos with colours extracted from plants, animals and minerals are distinct from other tribes of Northeastern region of India. Besides dyeing yarns or threads and garments, herbal dyes are also used for colouring crafts and for making body tattoos. Clothing of all types is woven on back strap loin looms (Figure 2) and weaving is an exclusive occupation of women, who make clothes for men and for themselves. Cotton (Gossypium herbaceum L.) and eri silk (Samia ricini Donovan) are the traditional sources of yarns or fibres for weaving garments.

The commonly used dye-yielding plants include Baphicanthus cusia (Nees) Brem. (family Acanthaceae), Marsdenia tinctoria R. Br. (family Asclepiadaceae), Indigofera tinctoria L. (family Fabaceae), Croton caudatus Geisel. (family Euphorbiaceae), Morinda angustifolia Roxb. (family Rubiaceae) and Curcuma longa L. (family Zingiberaceae). Red dye is extracted from the lac insect Laccifer lacca Kerr. (Lacciferidae). Elsewhere, I have written about the dye-yielding plants of the Karbis and traditional dyeing of yarns and garments (Teron and Borthakur 2012). In the following paragraphs, I describe the traditional knowledge of dyeing duk, the facial tattoo, with indigo and its cultural significance.

Sibu (Marsdenia tinctoria R. Br.; family Asclepiadaceae) (Figure 3) is the traditional source of indigo dye used for the duk tattoos and for dyeing pini (lower garments of Karbi women). Sibu can be easily propagated by seeds and its management can be achieved without much expertise and expense. Women are the users and custodians of this indigo plant.

Traditional knowledge of making duk, facial tattoo of women

In the olden days, it was a tradition for every Karbi woman to have duk or facial tattoos, as it was believed to confer them status, purity and pride. Making duk is an elaborate process that touches upon their religious practice. The expert tattoo maker was always a woman. Duk is usually made in the morning of a clear sunny day as the woman making the tattoo can have better view and avoid inflicting unnecessary pain on the recipient. Also, in the morning hours the weather remains cool which is believed to be less painful to the recipient. As part of the tradition, the recipient offers a bottle of hor (distilled liquor) and horlang (rice beer) to the tattoo maker, which she then offers to her kuru or predecessors, seeking their blessings so that a quality tattoo is produced on the recipient. She then takes spines of rattan (Calamus sp.)—one spine on each hand—and without damaging inner tissues pricks the skin of the recipient from the forehead down to the chin passing along the nose. Blood droplets ooze out of the pricked skin.

Fresh tender leaves of sibu are ground in a wooden mortar and the juice is applied along the pricked skin with a feather or puff of cotton. After a few days, when the skin has healed, if the tattoo is not of the desired color and intensity, the process is repeated; usually there are not more than three rounds of pricking. A good tattoo is black or deep blue, in a line from forehead to the chin passing over the nose (Figure 1). On successful tattooing, the recipient has to honour the expert with a pair of pini (lower garment of women dyed with sibu) and pekok (upper garment); no cash is paid for the service. We interviewed about fifty three women who had taken duk, none of them reported any adverse reactions of skin after taking the tattoo. Making duk inflicts pain on the recipient, but it is part of the cultural heritage of Karbi women to undergo the ordeal.

Cultural significance of Duk

In the past, on attaining puberty girls received duk to substantiate their adulthood. Girls were not married off before receiving the facial tattoo; duk thus made them eligible for marriage. Further, duk was considered as symbol of purity and honour as girls having duk could serve food and other eatables to pinpo or dignitaries of traditional institutions. It was believed that duk was not a mere tattoo but possessed the divinity to purify the soul: girls who had not received duk were considered immature and unholy. During tattooing, the expert chanted sacred verses relating to a deity so that the recipient was cleansed of any impurity contacted during birth. The concept of "unholy" stemmed from their world views: according to Karbi religious beliefs the amniotic sac, amniotic fluid and umbilical cord were considered impure and so a baby was also considered impure from religious standpoint. The menstrual discharge was also considered impure. On taking a duk, the girl was said to be free from impurity and became divine.

Acknowledgement

The authors are indebted to all the Karbis informants who shared their knowledge and to local guides for their able guidance and hospitality during our field study.

Further readings

Guljarani, M. L., 1992. Introduction to Natural Dyes, Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi.

Guljarani, M. L., 2001. Present status of natural dyes. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res., 26: 191-201.

Mahanta, D. and S. C. Tiwari, 2005. Natural dye-yielding plants and indigenous knowledge on dye preparation in Arunachal Pradesh, northeast India, Current Science, 88(9): 1474-1480.

Phangcho, P. C., 2001. Karbi Anglong and North Cachar Hills—A study of geography and culture. Printwell, Diphu, Karbi Anglong.

Teron, R. and S. K. Borthakur, 2012. Traditional Konwledge of Herbal Dyes and Cultural Significance of colors among the Karbis Ethnic Tribe in Northeast India. Ethnobotany Research & Applications, 10:593-603.

About the Authors

Robindra Teron is a Sr. Assistant Professor in the Department of Life Science and Bioinformatics, Assam University, Diphu Campus, Diphu, Karbi Anglong, ASSAM - 782 460, India. Email: robin.teron@mail.com

SK Borthakur is a Professor in the Department of Botany, Gauhati University, Guwahati, ASSAM - 780 014, India.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal