Colours in Laos

By May Bass

In August, 2013, a friend and I visited Laos for three weeks. Our main reason was to see Laotian textiles and, if possible, natural dyeing. I want to emphasise that the following account is of a demonstration rather than an observation of everyday natural dyeing. This of course had time constraints, particularly where soaking of fabric and dye materials were concerned. Language also posed a problem. We had a good interpreter but he was not from a textile background and he could not answer all of our questions. No mention was made of mordants but I did notice that all the soaking and boiling was carried out in aluminium pots. For those who are interested in learning more about textiles in this part of Laos I strongly recommend the book Lao-Tai Textiles: The Textiles of Xam Nuea and Muang Phuan by Patricia Cheeseman. It is an excellent book.

Our demonstration took place in Xam Tai, a small village in the Northern Province of Houaphan in Laos. We were there in the monsoon season, with temperatures in the 30s Celcius (86-104F) and high humidity. The journey from Luang Probang to Xam Tai was not easy. The terrain is mountainous, with steep and winding roads which were wet and pot-holed due to torrential downpours. We travelled three days on a crowded bus with numerous delays: one day we waited eight hours for the gear box to be mended and another four hours while brakes were repaired.

When we finally arrived in Xam Tai, we found a beautiful and shaded place, where ducks waddled, chickens strutted and the River Nam flowed peacefully past. The demonstration was in the workshop and garden area of Mrs. Phuit, a master dyer. She proceeded to demonstrate how she dyes skeins of silk using the natural plants that grow close by and how later they are woven into the most beautiful pieces of silk you can imagine. Mrs. Phuit prepared the open fire, stacked logs for fuel and gathered the material and equipment she needed.

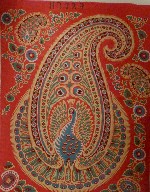

We were first shown what looked like small pieces of broken sticks, which we are told is khang. I recognised it as Stick Lac, the secretion of a female insect (Cocus lacca) in which she lays her eggs that is found on the branches of trees. The pieces were placed into a large container and pounded into a powder. Water was added and it was left to soak. After soaking, it was boiled and squeezed through a double layered piece of mesh material which resembled an onion bag. The silk yarn was added and the pot brought to the boil again for the dye to do its magic.

|

Piece of Khang (stick lac). The hole shows clearly how the insect has secreted the lac around a twig base. |

Mrs. Phuit pulverizing stick lac. |

|

|

| Photograph Copyright by May Bass | Photograph Copyright by May Bass |

On a table were some prickly seed pods which resemble the pods of the sweet chestnut. Mrs. Phuit shook out the small brown seeds which are called maak saet. They are seeds from the annatto bush (Bixa orellara). They were left to soak, and later boiled in an aluminium pot for about half an hour. Silk was then added and left to soak, yielding a beautiful orange colour. The silk was then rinsed and hung to dry.

The next dye that Mrs. Phuit demonstrated used a large bunch of fresh green leaves, called horm, which is the indigo-producing plant species Strobilanthes flaccidifolius. In the past I have only associated indigo with the colour blue so I was curious. The leaves were pulverised into a mash and water added. The mash was squeezed through the mesh fabric and all the liquid poured into an aluminium bowl. The mixture resembled a ready-to-use indigo vat -- all frothy but green! Silk was left in this solution for only a short while and a beautiful bluey green colour was the result. In her book Lao Textiles of Xam Nuea and Muang Phuan, Patricia Cheeseman quotes a very similar recipe where slaked lime is added. She also explains that if the silk is left in the solution for a longer time, different shades of green result and if it is left still longer the colour will turn to grey.

Mrs. Phuit next demonstrated dyeing a skein of silk silvery grey. She chopped some wood called nangben into small pieces, which she placed into a pot and with a scoop of solution from a huge vat where the bark pieces of the same tree have been left fermenting for three months. The pot was then put on the fire to boil and the liquid soon turned to brown. When that happened, the dye was poured onto the silk and left to soak. When the silk itself was brown, it was plunged into a bucket of grey coloured mud where it was again left to soak. The result was a very beautiful silvery grey colour.

The last demonstration was the dyeing of the skeins yellow. Pieces from the nangmarklinmai, which I understand is the bark of the jackfruit wood (Artocarpus heterophyllus) were put in a pot to soak and then to boil. After the pot was taken off the fire and cooled, the silk was added and it was boiled again. Mrs. Phuit was not satisfied with the resulting colour and decided to add another colourant, haem, which is the climbing turmeric (Arcangelisia flava). The result was a stunning golden yellow.

When all was finished, a celebration was in order. Mrs. Phuit suddenly produced a rather large bottle of alcohol. Glasses were filled and all good wishes expressed. It was time for us to thank her and the interpreter for such a wonderful and interesting afternoon.

About the Author

May Bass lives in a small village overlooking the sea near Wellington, New Zealand. She has a passion for felt work and more recently has developed one for natural dyes also. At present she is endeavouring to marry the two.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal