Eco Printing with Native Plants

By Wendy Feldberg

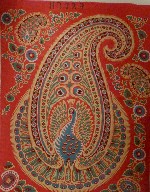

Eco printing as art

Natural dyeing offers me a way to integrate two lifelong passions: fiber art and gardening. As a fiber artist, I look to nature, wild and cultivated, to provide both thematic content and materials for my art, especially from the rugged Boreal landscapes of eastern Ontario where I live (USDA gardening Zone 4). My current interest is in 'eco' printed textiles and papers for botanical scrolls in the form of embroidered wall art and Artist Books.

Acer saccharum (Botanical Scroll series), 2013

Eco printing, a contemporary application of traditional natural dye knowledge, is a direct or contact printing technique that extracts natural dyes from plant materials, depositing them as prints onto the substrate. While dyeing whole cloth evenly in one color is usual in traditional natural dyeing, my aim is to obtain prints in a variety of shapes and colors with a strongly impressionistic or abstract character.

My typical art process is to lay down marks on fiber surfaces by printing, painting and/or stitching, responding intuitively to successive layers of colors and marks, always seeking to express with the cloth or paper some response to nature. I use native and bioregional plants for dyeing, and include favorite "introduced" plants from garden, forest and wayside to "eco" print paper and mostly recycled natural fibers.

My first experience with eco prints occurred serendipitously when a fall maple leaf printed itself onto an iron-mordanted textile that I was rust-printing in the sun. That first eco print became part of my series of botanical scrolls about North American native plants, a rust and plant-printed artist book about the iconic Canadian sugar maple, Acer saccharum. The eco printing process in brief Eco printing is a kind of alchemy, as much art as it is science. Several interacting factors influence the final print: the age and part of the dye plant, the plant's growing conditions, the textile fibre (cellulose or protein), the choice of mordant (e.g., alum, iron), the choice of dye assistants, time for resting, etc. Regardless of these other factors, direct and firm contact between plant and substrate is key to a successful eco print. Plant materials (along with branches, barks, rocks or metals, too) should be securely wrapped in a pre-mordanted textile or layered between sheets of watercolor paper; the bundle is tied tightly with string and perhaps weighted with a brick, then steamed over water or simmered in water or natural dye. Different print effects are obtained by layering, tying, folding, clamping or stitching metals, rocks, twigs, etc. onto the substrate. The process extracts the plant pigments onto the textile or paper, which is then left to cool in situ. If allowed longer resting time, the textiles or paper can be eco printed by composting them in the earth, rusting with metals in acid (e.g. vinegar) or solar-soaking in water or dye. With thoughtful dye plant combinations and use of mordants, predictable prints as well as "surprises" can result. Terminology A rose is a rose by any other name... The terms "eco printing," "eco dyeing" and "contact printing" each describe the same end result. "Eco printing" tends to describe a method of transferring a design; "eco dyeing" focuses on the chemical bonding that results in a dye-printed surface; "contact printing" refers to a method of printing. (Incidentally, not only fiber surfaces will eco print—wood, stone, plastic and metals in the fiber bundles have also accepted dyes.) I use the epithet "eco" to allude to a preference for native dye plants, responsible plant collecting practices, stewardship of the natural environment, recycling of found natural materials for art and the avoidance of toxic mordants (such as chrome and tin) and of known poisonous plants. A Little History Eco print effects may be familiar to readers from several sources. You may have noticed that in the autumn when rains force tannin-rich leaves to fall and stick onto the wet concrete sidewalk, the direct contact between concrete acids and leaf tannins often causes the leaves to print their shapes, especially in dark grey. You may have experimented with the all-in-one dye bath method explained by Jenny Dean in Wild Colour as a way to create special "pattern effects" by placing plants in direct contact with the textile. Dean notes that if "more than one dyestuff is wrapped into the fabric, a little colour from each dyestuff runs into the other and overlaps" (Dean 1999, p. 52). In books, blogs and academic papers, other practitioners have recorded their contact print processes more extensively, notably Canadian dye scholar, Karen Leigh Casselman (2004), who coined the term "eco dye" and was mentor in alternative natural dye processes to the well-known eco-print artisan and author, India Flint (2008). Flint's original inspiration was European folk traditions for dyeing eggs with plants. Her subsequent use of the term "eco print" has now become standard among international enthusiasts who are developing eco print techniques on their home grounds and reporting their work to growing interest on the internet. Successful native plants for eco printing After downsizing my house and garden recently, I began developing a bioplan for a smaller suburban garden that favours native plants in a modestly naturalized setting, emphasizing heat-, drought- and cold-tolerant plants useful for dyes and acceptable to the neighbours! Native plants are appropriate for low-maintenance plantings in pesticide-free and compost-rich suburban gardens, and for attracting neighborhood-friendly wildlife such as butterflies, birds and pollinating insects. Favorite non-native, eco dye stalwarts have a place, too—two examples among many that I use are red Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) which prints blues, greens, yellows, browns, oranges, even pinks in the fall (though never reds!) and Smokebush (Cotinus coggygria) for its ever-changing range of yellows, oranges, blues, purples, greens and browns in autumn leaf prints, including lovely dots and mottles. My new garden already contains a respectable collection of former-garden transplants as well as resident "old friends": native and bioregional plants along with typical "wildlife garden" features including a pond, stonework, small (dead tree) snags, rocks, bird feeders, nesting boxes and bird baths. The largest tree is a sugar maple (Acer saccharum) that provides tans and browns from the seeds and greys and blacks from leaves and twigs. Old native crabapples (Malus sp.) supply spectacular yellow and teal-green prints in spring from blossoming branches. Native shrub plantings are cedar (species and dye color to be determined come spring), Common Elder (Sambucus canadensis) which gives greens from leaves and purples from berries; and Red Osier Dogwood (Cornus stolonifera), the latter a traditional quillwork red dye among Algonquin First Nations. Other trusty dye sources are Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) for greens from the leaves, pinks, purples and reds from the berries; and tannin-rich Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) for pinks and reds from the fruits, yellows and chartreusey greens from the leaves. Besides gathering my own garden plants, I routinely (and cautiously) forage for windfallen plant material (both native and introduced) in neighborhood streets and parks, along riverbanks and in the nearby forests of the Gatineau Hills. Among the dye-rich trees and shrubs that can be foraged in my new neighbourhood are Catalpa speciosa and Gleditsia sp. (Honey Locust), for brown prints from the tannin-rich pods; Sweet Gum (Liquidambar styraciflua) for a range of mottled greens, yellows and an occasional navy blue; Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) for rich deep yellows from the leaves, rich browns from green fruits); various roses (especially the "introduced" Rosa rugosa) for greens from the leaves, a somewhat fugitive coral-pink from the hips (but how to obtain that bright orange-red of rose hip jelly?); Purple Sandcherry (Prunus cistena, a species of native wild Black Cherry, Prunus serotina) for dark teal-blues and greens; Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) for dark greens and purples, deep greys and blacks; finally, though not a Zone 4 native, the humble marigold (Tagetes sp.) delivers generously and with little persuasion a powerful dose of orange from blossom and green from calyx. Many of my smaller understorey plants, shade and sunlovers alike, were known in local First Nations dye traditions and yield eco print colours that replace European sources like madder red, weld yellow and woad blue. For colors from these non-natives and from natives unhappy in Zone 4, I prefer to buy powdered dyes, which I paint like inks or sprinkle on the substrate. Examples of understorey plants for eco prints are Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and Coreopsis sp. (e.g., C. verticillata and C. lanceolata) for oranges and reds; Canada Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) and Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) for shades of yellow (plus tannin mordant from sumac); Violet flowers (Viola sp.) for teals and turquoises (with deeper colour from frozen blooms); and from Black-eyed Susan blooms (Rudbeckia hirta), orange-yellow-brown—with a tad of green! Other First Nations dye plants useful for eco prints are from the alder species, e.g, Alnus incana for a rich browned red; Cottonwood (Populus sargentii) for yellow, elderberries (Sambucus sp.) for black or purple; and blackberry fruit (Rubus sp.) for deep blue or magenta (when smooshed or painted onto a mordanted surface); blackberry leaves for complex deep greens; and several native ferns that print green. An indigo-type blue is hard to obtain from natives. But experiments to trick out the blues from available non-native plants are fun if approached as a non-purist. Red Cabbage from the grocery store or kitchen garden gives a range of lovely blues, depending on the fiber and mordant. Creeping Bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides), is an invasive, non-native pest for some but a "dye beneficial" for me, making a fine blue print from the blossom as well as adding welcome blues to vase and garden. Turquoise and sometimes even a navy blue arrives along with purples and greens from eco printed Tall Bearded Iris blooms. Designated as a Canadian heritage plant, this iris was probably an early European introduction via the very old Iris germanica. Like other European iris introductions, Siberian Iris (Iris siberica) also gives great blues. Now with protected status, the common but lovely Iris versicolor, the Fleur de Lys emblem of Quebec, will always have a place in my garden along with the Sugar Maple. Furthermore, freezing these "blues" and others seems to bring out deeper color and more of it. Come summer, I look forward to experimenting with blues from the magnificent perennial, False Indigo (Baptisia australis) a North American native which has given me yellow eco prints from leaves, later greened with iron; and with Dyer's Knotweed or Japanese Indigo (Persicaria tinctorium), a non-native annual hardy in Zone 4. (This is not the invasive form, Fallopia japonica, although the latter's roots give orange-yellow dye, I hear. Incidentally, the hardy and weedy Polygonum aviculare, is said to yield blue dye. Since it is a common weed hereabouts, it will go on my foraging list of "dye beneficials".) I look forward to more eco print experiments with native plants for dyeing in my suburban wildlife garden and to learning more about the dye properties of native plants and of non-native "dye beneficials". Is a garden ever finished? Characteristics of the eco printed surface Natural dye tradition confirms that almost any plant will yield some color; also that plant color does not necessarily indicate dye color. For an eco print, yellow is a safe guess—but not the last guess because fortune favors the curious and the risk-taking eco dyer! An intriguing and attractive characteristic of an eco printed surface is the tendency of plant pigments to separate into unexpected constituent colors, giving impressions of "broken color" on the substrate, with patternings and colourings of a spontaneous nature. These effects can be made more predictable by the selective use of mordants (pre- or post-dyeing) and dye assistants such as iron or copper, by applying acids (e.g., vinegar) or alkalis (e.g., ammonia) to shift pH, or by combining dye plants in the bundle in order to mix new colors right on the substrate. An example is pH-sensitive Red Cabbage which eco prints blue with alum; when splashed with vinegar and placed nearby Goldenrod blooms or some Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) dye powder, it will produce a mingled range of greens and blues; when printed beside the yellows it will produce blue-reds. Most of the dyeing and overdyeing tricks of the traditional dye trade can be adapted to eco dyeing. However, not all the colors predicted for traditional dye applications will necessarily appear in the eco print process. For example, the autumn leaves of Young Fustic (Cotinus coggygria) print blue, orange, red, and yellow; Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) in September prints deep yellow from the blossom but green from the leaves. The contact print process often allows pigments to emerge as individual colors, separations that are lost in a regular dye bath. For example, a blue flower such as Tall Bearded Blue Iris (containing delphinin, an anthocyanin pigment) can contact print blue, green, purple and turquoise all at the same time on a substrate. The same blue iris flower, when processed in the artist's traditional method (i.e., squeezing iris juice onto an alum-mordanted linen cloth that acts as a color reservoir when soaked in glair) yields a uniform green with alum and a uniform bluish purple without alum. Prepared in an immersion dye bath, the Tagetes flower head, calix and all, will yield deep golden yellows or oranges. Contact printed on a protein fibre (for example, silk), the Tagetes petals dye-print a range of yellows and oranges while the calyx (even when dried) dye-prints dark green. Similar color separations occur with Smokebush, Japanese maple and Sweet Gum leaves in fall. Thus, any given plant in season could be host to a range of pigments which, with the appropriate processes, dye assistants and substrates, can be induced to reveal themselves as individuals. Native And Introduced Plants for Eco Printing These plants supply reliable colour for contact printing. Many others yield useable colour. Experiments (and the taking of good notes) are the way forward! References Beresford-Kroeger, Diana, 1999. Bioplanning a North Temperate Garden. Quarry Press, Kingston, Ontario. Cardon, Dominique, 2007. Natural Dyes. Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. Archetype Publications, London. Diadick Casselman, Karen, 1993. Craft of the Dyer. Dover Publications, Inc., New York. Cannon, John and Margaret Cannon, 2002. Dye Plants and Dyeing. A&C Black, Publishers, London. In association with The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Dean, Jenny, 1999. Wild Colour. The Complete Guide to Making and Using Natural Colour. Octopus Publishing Group, Ltd. (Random House, New York). Feldberg, Wendy. Threadborne. www.wendyfe.wordpress.com _____________ 2012. "The Alchemist" in Hand Eye Magazine, March 2012. http://handeyemagazine.com/content/alchemist _____________ 2012. "Eco Printing: Contemporary Perspectives on Natural Dyeing"

in Fiber Art Now magazine, Spring 2012. _____________ 2013. "Unearthing Eco Dyes" in Fiber Art Now magazine, Summer 2013. _____________ 2013. "Eco Printing With Rust and Plants" in Somerset Studio magazine, July 2013. Flint, India, 2008. Eco Colour. Botanical Dyes for Beautiful Textiles. Interweave Press, Colorado, USA. Haar, Sherry, 2011. Eco Printing: Dyeing and Printing With Plants. Sustainable Practices for Colour Effects. http://krex.kstate.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/9118/Haar%20Eco%20Prints%202011%20KSU%20Sustainability.pdf?sequence=1 Kadolph, Sara J. and Karen Diadick Casselman. "In The Bag: Contact Natural Dyes" in Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 2004 22:15.DOI 10:1177/0087302X0402200103 (online) McGrath, Judy Waldner. 1977. Dyes from Lichens & Plants: A Canadian Dyer's Guide. Van Nostrand Reinhold Ltd. Toronto. Mc Guffin, Nancy, Ed., 2004. Dye Plants of Ontario. Burr House Weavers and Spinners Guilds Plants For A Future. (PFAF). Online database. www.pfaf.org Richards, Lynne and Ronald J. Tyrl, 2005. Dyes From American Native Plants. A Practical Guide. Timber Press, Inc. Portland, Oregon. About the Author Of Orkney heritage, Wendy Feldberg is a fibre artist now living in Ottawa, Ontario (Zone 4, USDA). Her current interests are in creating art textiles and Artist Books eco printed with plant pigments.

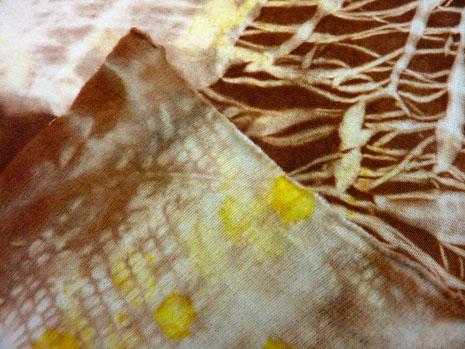

Native plants laid out on pre-felt before bundling: Sumac, Monarda, Coreopsis

Pre-felt bundle, post printing

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Silk scroll, Osage orange dye powder, Red Cabbage leaves, rust, vinegar.

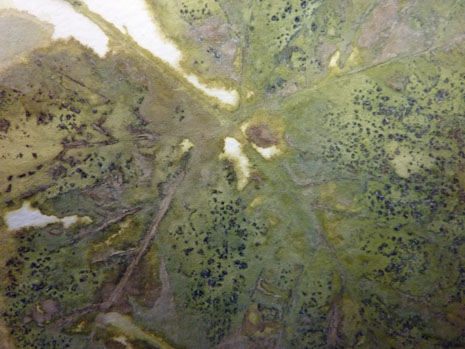

Coreopsis verticillata with Rhus typhina on linen

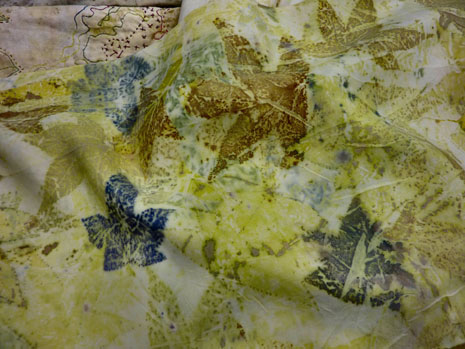

Eco printed wool collection.

Smokebush, Iris, Eucalyptus, Calalpa pods, Black Walnut, Japanese Maple.

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Iris on silk with iris green cords

Native plants on handwoven wool.

Sumac, Goldenrod, Purple Sandcherry, Marigold and Rugosa Rose

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

A corner in the author's June garden

Goldenrod (Solidago Canadensis) and Sumac (Rhus typhina) in September

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Photograph Copyright by Wendy Feldberg

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal