Ajrakh: Invoking History And Celebrating The Subaltern

By Shelly Jyoti

My first experience of creating Ajrakh artworks was when I was researching my visual art project titled "Indigo Narratives" in 2008. Inspired by a literary text Neel Darpan written by Deenbandhu Mitra (1860) on the plight of indigo farmers, these works were narratives presented through Ajrakh installations and sculptural artworks. The works further explored Ajrakh textile traditions with indigo as a plant, a color and a dye.

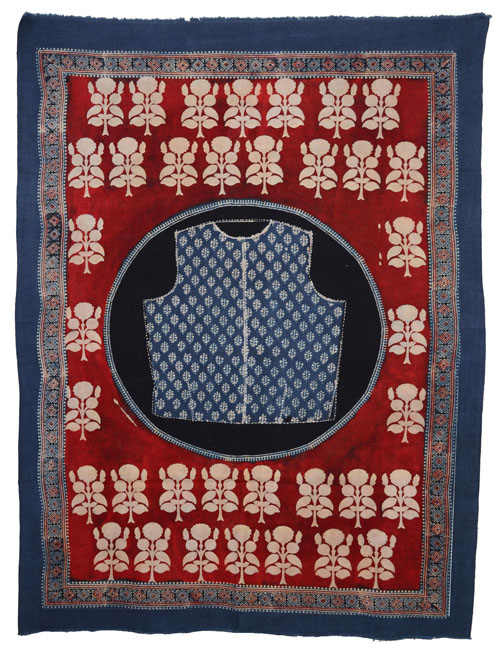

42x60 Inches. Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi.

Between 2008 and 2014, I created two exhibitions, "Salt" and "Indigo," both inspired by political movements in India's freedom struggle. In both efforts I used khadi (hand-woven cotton) for Ajrakh printing, dyeing and needle work. I selected the patterns from Ismail Mohmd Khatri's studio. He is a ninth-generation master craftsman in the art of traditional Arjakh block printing. His sons Sufiyan and Juned continue to cherish their legacy in his workshop in Azrakhpur, Bhuj, Gujarat.

Installation view at India International Center, New Delhi, India.

Ajrakh is one of the oldest types of block printing on textiles still practised in parts of Gujarat and Rajasthan in India, and Sindh in Pakistan.The word Ajrakh carries many meanings. It is also linked to azrakh, the Arabic word for indigo, and a blue plant, Indigofera tinctoria, which thrived in the arid climate of Kutch until the 1956 earthquake. The popular story amongst local printers is that Ajrakh means "keep it today." Nomadic pastoralist and agricultural communities like the Rabaris, Maldharis, and Ahirswear wear Ajrakh cloth as turbans, lungis, or stoles. It was gifted on the Muslim festival of Eid to bridegrooms and on other special occasions. The colors of a true Ajrakh textile are fast.

The history of Ajrakh can be traced to the ancient civilizations of the Indus Valley, around 2500 BCE to 1500 BCE. A bust of the King Priest excavated at Mohenjodaro has a shawl draped around his shoulders. This shawl is believed to be an Ajrakh, decorated with a trefoil pattern interspersed with small circles, the interiors of which are filled with a red pigment. The same trefoil pattern has been discovered in Mesopotamia, as well as on the royal couch of Tutankhamen. This pattern, which symbolises the unity of the gods survives as the cloud pattern in the modern Ajrakh. Small fragments of an Ajrakh more than 500 years old have been found at Fustat, Cairo's first Islamic settlement. The largest collection, some 1200 scraps, is at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England. It is presumed by the curators that the many tailoring and mending seams in the pieces indicate that Ajrakh was a utilitarian garment cloth rather than a luxury good, and that it was desirable in Egypt because of the high quality of its colorfast dyes and the intricacy of its designs.The art is believed to have spread across the Indus River to the Thar desert in the 16th century CE. The then ruler of Kutch, Rao Bharmalji I (1586-1631), invited the cloth-printing Khatri artisans from Sindh and gave them permission to settle and earn their livelihood anywhere in Kutch. They were given land by the state and spared taxation on their produce. Their descendants have been living here and practising the Ajrakh traditions since 1600 CE.

From a technical perspective, Ajrakh is a very demanding and laborious form of cloth-printing and resist dyeing, in which designated areas in the pattern are pre-treated to resist penetration by the dye. Ajrakh designs, in terms of variety and arrangement, are limited and dominated by geometrical shapes. However, the Ajrakh cloths evenly printed on both sides are among the finest examples of textiles.

|

Ajrakh artworks in process. Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi, Gujarat, India. |

||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Shelly Jyoti |

The process of creating an Ajrakh is complicated, involving a variety of steps, from pre-soaking the cloth in a mix of camel dung, soda ash and castor oil, to mixing the dye-resistant pastes made of gum and millet flour, to blending secondary dyes from an array of natural sources such as turmeric for yellow, rhubarb for brown, pomegranate skin for orange, madder root for red and a boiled syrup of scrap iron, chickpea flour and sugar-cane molasses for black.

Water is vital to the production of Ajrak cloth as it is prepared, mordant, and dyed. At each stage the character of the water will influence everything, from the tones of the colors to the success or failure of the entire process. After the 2002 earthquake in Kutch, the water table shifted and the water has impurities, a development which adversely impacts the printing of textiles in Kutch. The artisans are seeking the help of the government to resolve this problem so that they can continue with their traditional craft.

Azrakh blocks, or Pors, are hand carved from the wood of Acacia arabica trees. Several different blocks are used to create the characteristic repeat pattern. Making the blocks is a considerable challenge since the pattern has to synchronize perfectly with the whole of the Ajrakh as well as cover those areas which must resist the dye. Block makers or poregars use the simplest of tools, and carve each block in pairs that register an exact inverted image on the reverse. There are very few Ajrakh block makers left now.

One of the most distinguishing qualities of this textile is that it has retained its traditional character through the challenging period of modernisation, and its established producers as well as customers remain loyal to the craft. It was temporarily sidelined by textiles involving modern, quicker methods of printing but because of the efforts of the master craftsmen and the increasing awareness among the urban people of the overall richness and value of environment-friendly natural dyes, this craft is slowly regaining momentum.

These recent scrolls of textiles utilizing Ajrakh printing/dyeing/needle work as artworks on khadi were on a title of my solo exhibitions "Salt: The Great March—Re-Contextualising Ajrakh Textile Traditions on khadi in contemporary Art and Craft" (2013-14). These works have been exhibited in IGNCA Indira Gandhi National Centre of the Arts (September 2013), IIC India International Centre (2014) and Dakshin Chitra, Chennai (2014). "Indigo Narratives" (2009-14, two women show) has been exhibited around the world in cities like Mumbai, New Delhi, Vadodara, Seattle, Miami, Chicago and Washington, DC.

Working with various media and drawing from history, my art celebrates the subaltern, the folk, and the voices of the unsung heroes which need to be sung again. My work as an artist is centered on historical iconographic elements within the cultural context of Indian history. I explore and construct the hermeneutics of period histories and the contemporary representation of socio-economic and political inquiry within my art practice. With my academic background in English with American literature, formal training in fashion designing and clothing technology, my artworks interconnects art, design and critical theories. I collaborate with the 9th or 10th generation of Ajrakh artisans who migrated from Sindh and Balluchistan in 1600 CE but still carry on with ancient textile traditions of printing and dyeing in Bhuj, Gujarat. Traditionally they work with Indigo and other natural colors. Invoking such traditions, I bring together khadi as a fabric, Ajrakh textile traditions and skill of the craftspeople giving my own interpretation in a visual form. My artworks are collaborative efforts supported by Juned Ismail Khatri and by his artisans (Sako Bhai, Rafiq Pandhi, Rahim Khatri, and Razak) at Azrakhpur, Bhuj. These artworks draw upon India's history, narratives of immigration and economic changes and document the 4500 year old technique of Ajrakh printing and dyeing.

Ajrakh printing unit at Ajrakpur, Bhuj, Gujarat, India.

I have also tried to capture the techniques and patterns of Ajrakh textile traditions on khadi—along with documenting women's wear in classic style belonging to the 21st century—in "Salt: The Great March" (2013-14) series. These artworks have been influenced by garments worn in the Mughal period in medieval India. In this series of five artworks on khadi, I am trying to capture the techniques and patterns of Ajarkh textile traditions on khadi and document the upper body women's wear silhouette in the classic style belonging to the 21st century. The five different contemporary silhouettes reflect the influence of the Mughul period, historically known as the Angrakha and Jama styles which were worn by men during the Mughul period in Medieval India.

34x50 Inches, Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi.

34x50 Inches, Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi.

|

Timeless Silhouettes: Blouses (2014). 60x60 Inches, Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi. |

||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Shelly Jyoti |

34x50 Inches, Ajrakh printing dyeing on khadi.

The 2D garments/artworks in the contemporary silhouette have a breast fit and are loose around the body. The waist to the hem has a flare made by stitching two or more panels stitching on either side. The bottom skirt is flared. The purpose of creating these 5 artworks of different contemporary silhouettes is both to document Azrakh patterns and styles that have been worn by women of India in the 21st century and to explore khadi fabrics as artworks.

To me, textiles created as artwork have a greater sense of preservation as a visual medium for documentary purposes than functional textiles. While both have symbolic purposes, my artwork challenges me to apply this vision of traditional pattern block and natural colors in the context of a socially and environmentally responsible design practice.

Shelly Jyoti (www.shellyjyoti.com) is a Delhi-based contemporary visual artist, fashion designer, poet and an independent curator.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal