Mordanting Cotton and Cellulose—Successful Methods

By Donna Brown, Diane de Souza, and Catharine Ellis

In the Spring 2010 Turkey Red Journal, we documented our collaborative studies on mordanting cellulose fibers, primarily cotton. Our research has continued and our studio methods have been refined since that article was published. This article describes results of experimentation and methods learned in two classes at Penland School of Crafts: one in 2012 taught by Charlotte Kwon (Maiwa) on "Natural Dyes" and the other in 2013 by Joy Boutrup1 and Catharine Ellis titled "The Art and Science of Natural Dyes."

We have also been involved with the Mayan Hands project "Tintes Naturales" (http://naturaldyeproject.wordpress.com/our-story/), working with a group of Mayan women in San Rafael, Guatemala to dye cotton yarns with natural dyes. Considerations of cost and availability of ingredients pushed us to look for simple, inexpensive methods to mordant cotton.

Indigo, Indigo, Pomegranate, Osage Orange, Indigo/Osage Orange

Row 2 (left to right):

Cochineal, Cochineal, Madder (Rubia cordifolia) Madder (Rubia cordifolia) , Indigo/Pomegranate

(Row 3): Undyed unmercerized cotton yarn

Considering the variety of mordant recipes available it is very difficult to know which methods are best. Some of the procedures we have reported in the past are better for printing or surface design techniques, while some steps reported in historical papers were found unnecessary when mordanting cellulose fibers for immersion dyeing. Based on the previous experiments, research into historical methods, Charlotte Kwon's and Michel Garcia's methods and consultation with Joy Boutrup, we narrowed down the variables to examine in order to test mordanting methods. Our goal was to achieve evenness and depth of color with good light fastness properties using natural dyes. All samples were dyed on mercerized cotton fabric and were scoured (see below).

The variables we studied were: (1) Type of treatment before mordanting; (2) Type of treatment after mordanting; and (3) mordant variation.

1. Treatment before mordanting

2. Treatment after mordanting

3. Mordant variation

The natural dyes used were: weld (dried Reseda luleola plant material @ 50% WOF), pomegranate (extract of Punita granatum @ 8% WOF), cutch (Catechu extract @ 12% WOF), cochineal (dried Dactylopius coccus @ 5% WOF), lac (Kerria lacca extract @ 5% WOF) and madder (dried Rubia tinctoria root @ 200% WOF).

These dyes were chosen because of their well documented performance in UV light and wash fastness tests. They have been used throughout history and the natural dye colors have endured.

| OIL TANNIN |

NO OIL TANNIN |

||

| 1 | 8% aluminum acetate dunged in chalk |

9 | 8% aluminum acetate dunged in chalk |

| 2 | 8% aluminum acetate | 10 | 8% aluminum acetate |

| 3 | alum/soda ash dunged in chalk |

11 | alum/soda ash dunged in chalk |

| 4 | alum/soda ash | 12 | alum/soda ash |

| OIL NO TANNIN |

NO OIL NO TANNIN |

||

| 5 | 8% aluminum acetate dunged in chalk |

13 | 8% aluminum acetate dunged in chalk |

| 6 | 8% aluminum acetate | 14 | 8% aluminum acetate |

| 7 | alum/soda ash dunged in chalk |

15 | alum/soda ash dunged in chalk |

| 8 | alum/soda ash | 16 | alum/soda ash |

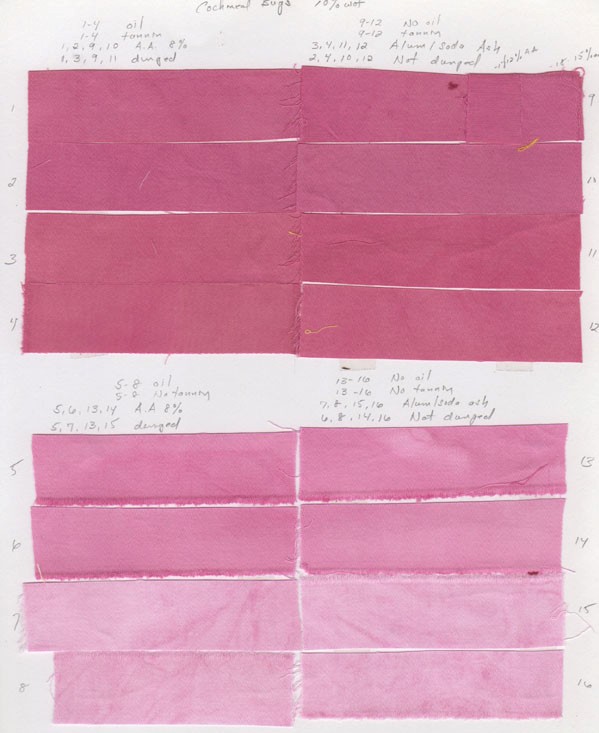

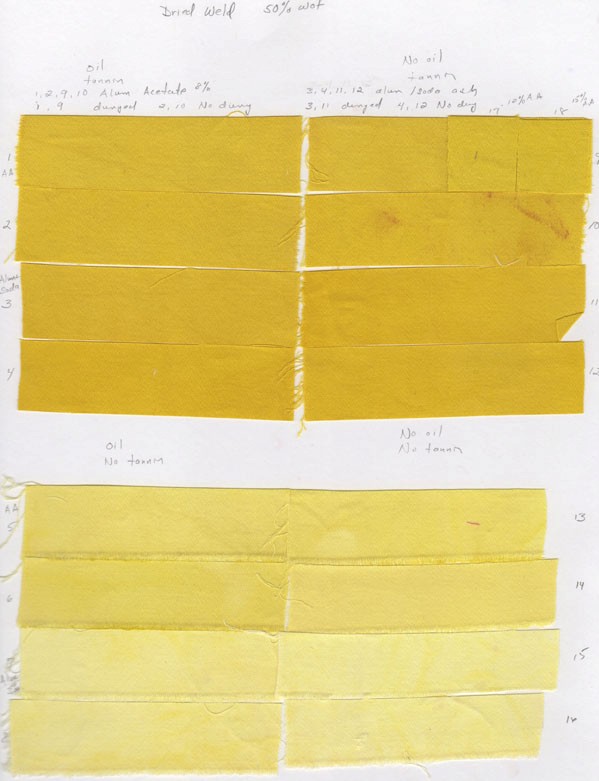

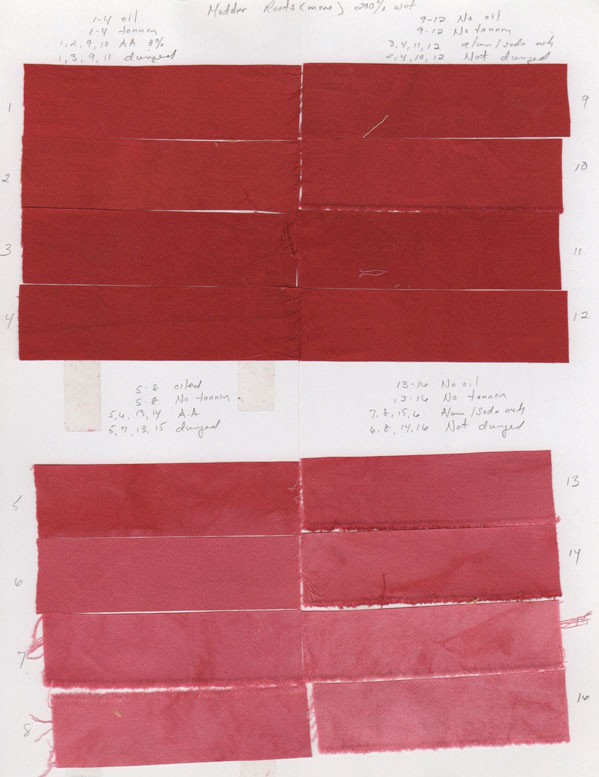

Samples correspond to Table 1 indicating mordant and fabric treatments

Samples correspond to Table 1 indicating mordant and fabric treatments

Samples correspond to Table 1 indicating mordant and fabric treatments

Observations:

The significant finding of our tests is that tannin is a very important component when immersion dyeing cotton. It not only improves the depth of color but also the evenness of the dye take-up. Tannin has an affinity for cellulose and aids alum based mordants to chemically bond with cellulose fibers.

The topic of tannin is complicated as there are many categories of tannin:

Clear tannins will not change the color of the fiber as much as red or brown tannins. The tannin color from all tannins will develop darker color if heat is used, which is an option. The tannin color will ultimately affect the natural dye color. The tannin step also increases the UV light fastness properties.

In reviewing the cotton fabric samples, turkey red oil and dunging with chalk do not appear to have any benefit. The dunging step is beneficial if printing with mordants prior to dyeing.

Both mordant recipes worked well and there is very little difference between them in terms of colors produced and light fastness.

The light fastness of the dyed cotton was also evaluated. The two mordant recipes performed similarly. A "blue wool" test scale was used to measure the permanence of dye colors when exposed to light by comparing the degree of fading on the test strip to that of the dyed sample3. Again the tannin step improved the light fastness with both mordant recipes. The dyes tested were rated at 4-5 for light fastness. This rating is acceptable for dyed textiles and is also an indication of good choices of dyes used in the tests.

|

Blue wool test strip. Left side of strip was covered while right side was exposed to full sun for 30 days. |

||

|

||

| Photograph Copyright by Catharine Ellis |

In summary, the two different mordant recipes worked equally well for cellulose fibers. Dye results and

light fastnesses were nearly identical.

The key steps are good scouring, followed by a tannin treatment before mordanting (detailed instructions are provided at the end of the article). If cost is an issue, the alum/soda ash mordant is less expensive. Also the materials may be more readily available. That is why we chose this process for the Guatemalan dyers. While there may be other ways to effectively mordant cotton, what is presented here are methods that are working well for us to date. Our recommendation is to do your own experiments and find a process that works for you considering the steps in the process and costs involved. Keep good records and have fun with your natural dye projects.

Mordant Recipes for Cotton and all Cellulose Fibers:

Before mordanting cellulose two steps are critical: (1) scouring and (2) a tannin soak.

Step 1: Scour the fiber

For every 1000 g. of fiber add

1 - a neutral liquid detergent (synthrapol, Joy, Dawn): 20 ml or 2% by volume

2 - soda ash (sodium carbonate) 80 grams or 8% WOF

Simmer 1-2 hours

Multiple scourings may be necessary to completely clean the fiber. If after scouring the water is very brown repeat this step.

Step 2: Apply Tannin

Weigh gallic tannin at 10% WOF:

Dissolve the tannin in hot water (100°-120° F) and add to a bath with enough water to float the fibers freely.

Soak the wetted cotton fibers in tannin 1-2 hours. Stir occasionally.

Remove fiber and rinse in cold water. Dry.

Cotton Mordant Recipe using Aluminum Acetate

Weigh Aluminum Acetate at 8% WOF

USE CAUTION when weighing Aluminum Acetate, which is a very fine powder. Use gloves and mask. Dissolve Aluminum Acetate in hot water (120°-140° F).

Add mordant into pot. Add scoured wetted out fiber treated with tannin to mordant pot with enough hot water (100°-120° F) to cover the fiber in the pot. Soak for a minimum of 2 hours. Stir occasionally.

Rinse in cold water.

Dry the fiber.

Cotton mordant recipe using Potassium aluminum sulfate (alum) and soda ash

Make two solutions:

#1 - Dissolve potassium aluminum sulfate in water at 12% WOF

#2 - Dissolve soda ash (sodium carbonate) in water at 1.5% WOF

Mix the 2 solutions together in a large container because it bubbles up a lot. Wait until the bubbling stops before adding the fiber.

Add enough hot water (90°-140° degrees F) to cover the fiber in the pot. Add the scoured wetted out fiber treated with tannin.

Soak for 2 hours if the solution is hot. Cooler solutions should soak for 6-9 hours. Stir occasionally.

Rinse in cold water.

Dry the fiber.

1Joy Boutrup is a textile engineer and taught at Designskolen Kolding in Denmark. She introduced textile/dye chemistry and science to American textile artists through presentations at Surface Design Association conferences in Kansas City and classes at Penland School of Crafts.

2Mordants and dyes were purchased from Table Rock Llamas Fiber Arts Studio (www.tablerockllamas)

3Purchased from Talas - Item# TEC025001

References

Buccigross, Jeanne M. 2006. The Science of Teaching with Natural Dyes. BookSurge, Charleston, SC.

Dean, Jenny. 2010. Wild Color, Revised and updated Edition: The Complete Guide to Making and Using Natural Dyes. Watson-Guptill Publications, New York.

Knecht, Edmund and Fothergill, James Best. 1952. Texts chosen and extracted by Joy Boutrup from The Principles and Practice of Textile Printing. Charles Griffin & Company Limited. London.

Liles, J.N. 1990. The Art and Craft of Natural Dyeing. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN.

Wipplinger, Michele. 2002. Natural Dye Instruction Booklet. Earthues, Seattle, WA.

Maiwa website: www.maiwa.com. Grandville Island, Vancouver, BC.

About the authors:

Donna Brown is a production natural dyer from Colorado, instructor, and natural dye sales representative for Table Rock Llamas Fiber Arts Studio. She will be teaching this fall at Penland School of Crafts.

Diane de Souza lives off-grid outside of Taos, New Mexico and often teaches in the local area. Her blog is http://dyeing2weave.wordpress.com/.

Catharine Ellis is a textile artist and teacher from North Carolina, known for her work in woven shibori and dyeing. She is currently working collaboratively with Joy Boutrup to research, validate, and document natural dye processes for the studio dyer. http://www.ellistextiles.com.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal