How Colorfast is Fresh-Leaf Indigo?

John Marshall

From time-to-time the question of colorfastness comes up regarding natural dyes, and fresh-leaf indigo in particular. With the exception of mineral-based natural dyes, such as iron oxide in soymilk, all dyes, including synthetic dyes, will fade with prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light. The question is always, "How much fading is acceptable?"

I decided to conduct an experiment to find out just how much the colors produced from the recipes in this book [Singing the Blues] will fade. I contacted a number of friends around the country–some are experienced in natural dyes; others have scientific backgrounds; others are artists. All of them had their own unique skills to bring to the group.

We started by sharing the same seed stock from my garden to remove one variable. The same recipes were sent to each participant, along with the same woven swatches prepared in the same manner–again this was done to reduce the number of variables affecting our results. What I couldn’t control were the unique working conditions of each member of the group.

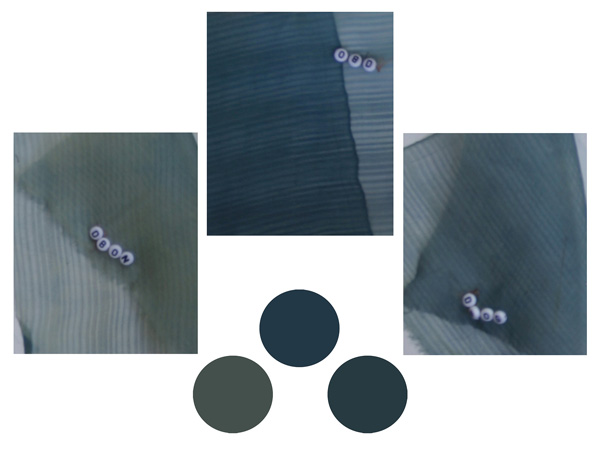

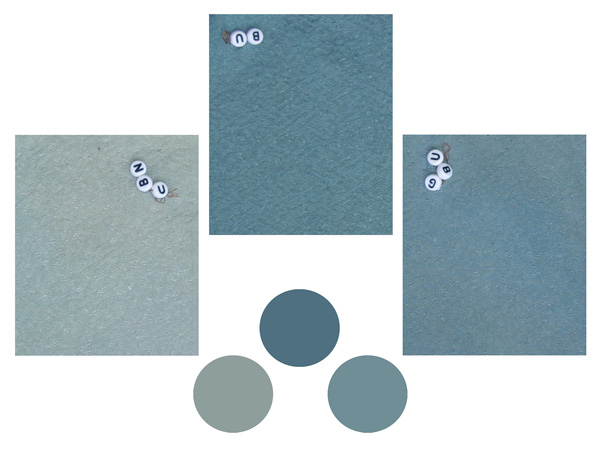

Once the participants finished dyeing the assigned dye samples, they mailed them back to me. I cut each piece into thirds. One piece, as a control in our experiment, was tucked away in a dark place to protect it from light. The second piece was given a coat of soymilk, and the third was left alone. Each piece was labeled with the dyer’s initials, the fiber content, the recipe used, and whether or not it received a coating of soymilk.

Each sample was clipped to a rack and hung outdoors with full exposure to the California sun for three months. They were exposed not only to sun, but sprinklers, birds and insects. That is likely to be far more abuse than you would give any textiles you have spent so much precious time in creating–but I wanted to see what would happen.

As mentioned above, many variables came into play even though we all used the same seed stock, recipes and fabric. In addition to the local water source and growing conditions, the actual pH achieved for the vat dyes was probably different for each participant, as well as how long each sample was allowed to soak in contact with the dye, whether the yardage was unbleached or natural, and probably other details I haven’t considered.

Photographing the samples to present to you also posed a problem. I’ve made every effort to color-correct the images you see here, but the characteristics of your monitor and printer (if you print a copy) will introduce more changes. Consider all these details as you reach your own conclusions regarding the desirability of any given color achieved.

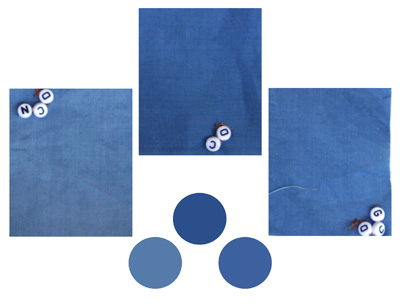

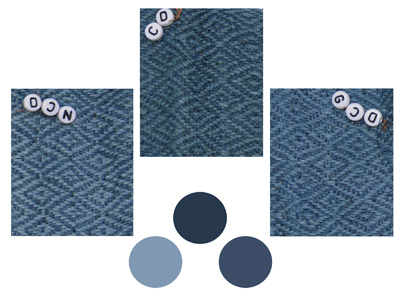

While the purpose of the experiment was to test for colorfastness in fresh-leaf indigo-dyed fibers, I thought it might also be interesting to see how these compare to fabrics prepared with other dyes, or with indigo from other regions of the world. I tested fabrics dyed with natural indigo from India, Guatemala, and Japan–they all fared about the same, so I included only one of them here. I also included synthetic dyes on synthetic fibers, and synthetic dyes on natural fibers. And as one more point of comparison, I included other natural dyes on natural fibers. These, too, faded at about the same rate as the fresh-leaf indigo-dyed pieces, so I also decided not to show them in the chart.

My rural town of Covelo, California, is 39.55º N (latitude) and 123.2481º W (longitude), with an elevation of 422.6 meters or 1400 feet. We have clean air and mostly cloudless skies throughout the summer months. Below are color swatches to show the results of our group’s efforts. If for some reason there was a range of results for the same fiber using the same recipe but from different regions, then I have included a sample of only the extremes.

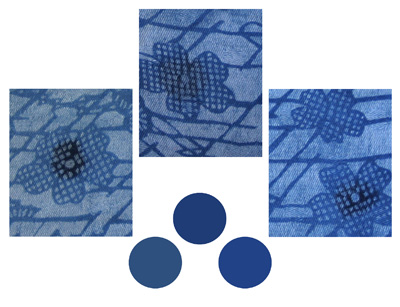

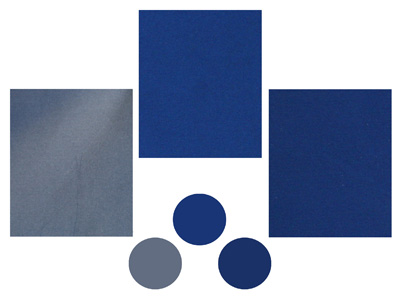

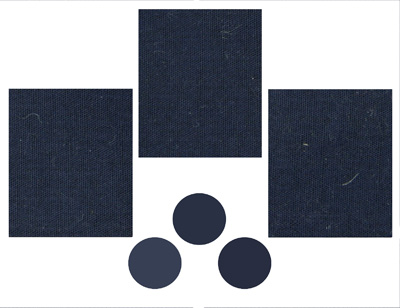

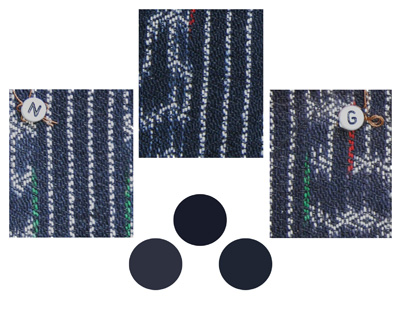

The squares are photos of the actual samples. The circles are an average of the shades found in each sample. The sample in the center of each grouping is the control–to the right is the sample treated with soymilk and to the left is the untreated sample.

|

Miscellaneous: Synthetic Dye on Silk Chirimen |

Miscellaneous: Synthetic Dye on Cotton |

|

|

| Photograph Copyright by John Marshall | Photograph Copyright by John Marshall |

Back to the earlier question: "How much fading is acceptable?"

The answer is truly up to you. All dyes fade with prolonged exposure to direct sunlight. That’s a given. Intuition tells us that even a little protection from UV rays makes a big difference, as the experiment presented here helps to prove. Keeping the finished textiles stored in a closet or box when not in use will certainly prolong their life–this applies as much to natural fibers as it does to natural dyes.

I have advocated the use of soymilk for treating dyed fabrics since the early 1970s. It is cheap, easy to make, and totally nontoxic, but it does have its limitations, though. As you can see from the tests on the previous page, it does make a significant difference in how quickly and to what degree the dye will fade–while it slows down the process, it doesn’t prevent it. I should mention at this point that a layer of soymilk applied to your finished piece will help to prevent wrinkling and cut down on soilage.

My feeling is that unless you’re producing upholstered lawn furniture, fading isn’t an issue. I produce high-quality dyed textiles, and I want to give my customers the best I can produce. To maintain that high quality requires some effort by the new owners to care for their investments. The clothing I produce is geared toward elegant day- and eveningwear. A few hours of standing in the sun during a summer wedding reception will do more harm to the mother-of-the-bride than it will harm the fresh-leaf indigo-dyed tunic she has chosen to show off. The colors offered by this unique process and the delight it brings my customers, as well as the joy I take in working with them, more than offset the somewhat limited lifespan of the colors achieved–just keep in mind, all colors fade.

The above article is an excerpt from John Marshall’s new book on dyeing with fresh-leaf indigo, Singing the Blues (http://www.johnmarshall.to/indigo/index.htm). It is based upon a group project, with each participant contributing their own, unique perspective and experience. The group included Deb McClintock (TX), John Britnacher and Marta Martas (OR), Cheryl Lawrence (WA), Pamela Feldman (IL), Donna Brown and the Denver Dye Study Group (CO), Sara Burnett (NY), John Marshall (CA). For more information, visit John’s web site at www.JohnMarshall.to.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal