Cochineal of the Canary Islands: In and Behind the Scenes

By Lorenzo Pérez

This article presents the history of cochineal production in the Canary Islands and my efforts to revive the industry, in which my family has been involved for three generations.

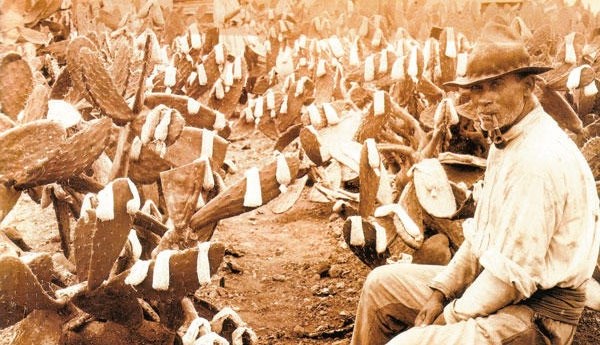

Cochineal production was introduced to the Canary Islands in 1825. Though the climate and growing conditions were ideal, Canarian farmers were reluctant to grow this crop. As Simón Benítez Padilla wrote, "it encountered great resistance from the farmers who were all convinced the new host they were offered with its prickly pears belonged to the obnoxious family of country plagues." Yet, once the first fears of the islander farmers were dispelled, the expansion of the crop was rapid. The Canary Islands offered a gentle climate, little rain and almost no storms for the prickly pear cactus which thrives with little water, much heat and not necessarily deep or fertile soil. Thus, in cochineal the Canarian farmers found a replacement their wine industry, which had faced a crisis for years.

The Canary Islands then experienced a golden age and all social strata benefitted from the cochineal production. The Canarian historian Agustín Millares Torres, who lived in this splendored time, wrote "The general situation of the country (Canary Islands) had continued improving given the high price cochineal was reaching in the foreign markets as well as the extension it had gained using the most ungrateful pieces of land. The working-class was no longer miserable nor idle. Those who filled paths begging for an insufficient daily wage were now requested by the owners and farmers to handle various operations concerning the planting and breeding of the insect needed. Not only did it occupy the strong arms of men and the light and weaker of women but also of kids, constituting the numerous offsprings a real welfare for their parents. The danger about this was that youth, driven by earnings, abandoned schools and instruction centers, contributing this way to rising the yet pretty high ignorance in the country."

One "fanegada" of land (5500 square meters or about half a hectare) produced 500 pounds (227 kilos) per harvest in Gran Canaria, and the intensive exploitation of a prickly pear farm provided two or more harvests per year. The working tools were normally rudimentary, Canarian women mainly took care of the gathering and cleaning of the product, while the men employed themselves in watching out for the plantations and the handcrafted techniques for drying the cochineal.

The quality of the cochineal produced was such that the Canaries soon achieved the leadership in exportations. Canarian cochineal was sent to the Spanish peninsula and abroad, mainly to England and France, through Marseille. In lesser amounts, some shipments were also sent to Morocco, Algeria, Holland, Gibraltar and the US.

The Decline of Cochineal in the Canaries

The first shipment of cochineal from the Canaries dates to 1832 was reported to be 1200 lbs. By 1838 that amount soared to 40,000 lbs. However, Mexico and Honduras maintained supremacy in cochineal at that time, both in quality and quantity. By 1860 the Canarian production had increased to 80,000 lbs. and by 1865 to more than 160,000 lbs. The productive "boom" ended around 1870 with exports of 600,000 lbs., half of this coming from Gran Canaria and the rest from the other islands.

When the cultivation of cochineal started out in the islands and began to spread, it was thought it would become the solution to the evils that had plagued the population. Unfortunately, the reality was different and the illusions of the Canarian farmers fell apart once again. History was repeating itself: early in the Canaries' economic history the sugar crops had failed, then wines, and now it was cochineal with the main difference being that as cochineal production had reached such high levels.

With the coming of aniline dyes (first mauve prepared by Perkins in 1856, then black formulated by Lightfood, and, in 1862, with the appearance at the Universal Exhibition in London of magenta and "solferino", a purple-red color, both produced from coal), the price of Canarian cochineal decreased from fourteen francs to eight.

This crisis in cochineal sales lasted until 1863, when the aniline colors were discovered to be unstable as well as dangerous to the health of the workers. The price of the cochineal then rose until 1868, when a lasting decline took place as the less-expensive aniline dyes displaced cochineal.

With the decline in the market, the cultivation of cochineal was eventually abandoned. This was due in part to the aging of the sector, the lack of generational replacement, the lack of regulation of the product in international markets, and also because of the indifference of the public Canarian institutions, which had shifted their attention to the development of agrarian products that were receiving European subsidies, such as banana and the Canarian tomato. Today, the Canaries produce very little cochineal–only about fifteen tons per year–and its production survived thanks to the effort of a few farmers, already retired, who keep gathering it as a hobby, because of the passion they have for it.

Current Situation: Canaturex is Born

My name is Lorenzo Pérez. One of the traditional farmers at the Universal Exhibition in London was my grandfather, with whom I shared many talks about cochineal in the Canaries. My whole life has been linked to this insect, as I grew up learning the manual techniques and the agrarian labors related to its cultivation. My passion for cochineal production is such that, although I have a degree in computer engineering, I felt a need to set forth and take advantage of the knowledge I had been given by my harvesting masters. I represent the third generation of a family of cochineal farmers and Canaturex is the brand I stand for.

"Times are changing" I thought "and somehow I have to find a way to preserve a historical and traditional cultivation", and so I got down to work.

Beginning with the current low production, how could we compete and make ourselves known again in the world? I needed to find out how to regulate cochineal production in the Canaries and link it to sustainability, quality, and traceability, three factors that are relevant today.

I started out registering the brand Canaturex. It cost me around 70€, and as I was completing the first steps of registration in the Patents Office, I received a letter from an attorney representing a large multinational company objecting to my using the name. I thought I would have to change the name of my brand, but the Patent Office gives the opportunity to present a defense statement, which I did. A month later, my registration was approved and my company won back its traditional name, Canaturex. I immediately sent a copy of the resolution to the director of this multinational company and kindly invited him to learn more about the cochineal of the Canary Islands.

Once the brand name was established, I consulted the Government of the Canary Islands to determine how to obtain quality recognition similar to other Islander agrarian products. I was informed that quality recognition was not possible because cochineal was not held to any quality regulation at that time. So, in 2011 I began work to establish quality regulation and use of the UPR (Ultra Peripheral Regions, the distant parts of European Union countries, such as the Canary Islands, Martinique and the Azores) logo and two years later, the Canary Island government approved quality standards for cochineal. Canaturex became the first brand of cochineal to use an agrarian quality logotype supervised by the European Commission of Agriculture.

The local media began reporting this news and some European dyers showed an interest in our product. Our quality was high and many dyers started to value it accordingly. Still, I wanted the most prestigious agrarian quality symbol, the PDO (Protected Designation of Origin), where the most renowned and emblematic products of each region are recognized. The records of the product must be impeccable in order to achieve this approval.

There were many obstacles to this achievement, including a severe shortage of active workers in the Canaries and the fact the cochineal trading at that time was dominated by customer focus on the lowest price possible, no matter what the conditions of production or the quality. This continues to be the case with the 90% of cochineal production worldwide.

Acceding to these market conditions would only lead to the total abandonment of cochineal in the Canaries. So now there was another series of hurdles to overcome to procure the Protected Designation of Origin certification. First, I needed approval from the Canary Island Department of Agriculture, then approval from the Spanish government, and lastly from the European Commission. These applications and presentations took months but eventually my application was approved and Cochineal of the Canary Islands was entered in the Community Register in February 2016 as a very well-deserved Protected Designation of Origin.

The main functions of a Protected Designation of Origin are: 1) defense against fraud, 2) differentiation and 3) development. The designation offers the customer an assurance of quality, helps ensure a viable livelihood to workers, and avoids conflicts in worldwide trading.

The quality standard for our cochineal requires a concentration of carminic acid at 19% or higher. Our product is reaching 22% to as high as 25% when humidity levels are at or under 13%. The coloring of the grains must be blackish tones, greys, reddish and should also include some whitish tones because of the cotton wax covering the females. To this end, our cleaning is carried out manually and the drying is strictly natural, in the sun.

The President of the Government of the Canaries expressed his satisfaction and noted the enormous success this represents for the archipelago. With all this, we are now hoping to relaunch the cultivation of cochineal in the Canary Islands and have access to the agrarian subsidies Europe provides to other quality products, as well as having access to local promotional programs enjoyed by other products of the islands.

Cochineal of the Canary Islands is the first natural dye in the world that can surely boast owning such an important emblem. It represents the importance of the region in relation to the product, the added value of a natural dye, sustainability and a new era.

Today, I am completely dedicated to my new plantations, as they are a big part of this official recognition. We are working there 24/7, cultivating color with a great passion. I also keep an old workshop for the manufacturing of dry cochineal, and I keep in touch with customers to be sure they are satisfied. I want them to know that by letting us be a part of their products our history remains alive.

Lorenzo Pérez is the CEO of Canaturex. He belongs to the third generation of a family linked to the cultivation and export of cochineal in the Canaries. He originally studied Computer Engineering, but after the European economic crisis of 2008, he decided to return to the field to work on the cochineal crops. The Canaturex web site is at http://www.canaturex.com/index_en.html.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal