The Dyer Botanist's Corner

By Eugenia Ron

The best wool of the world, produced by merino sheep, had its origin in Spain in the first century A.D. Subsequently, the Spanish wool industry was one of the country's main sources of wealth over a long period of time, but the lack of trade protections, competition with English and Australian wools and the invention of synthetic fibres almost put an end to it around the middle of the 20th century.

Wool craftsmanship (carding, spinning, dyeing and weaving) has had a strong revival throughout Spain in recent years. A number of artisans who work with their own designs also offer workshops in dyeing with natural dyes on cotton, silk or wool. Thanks to the success of these workshops, the use of dyes known since antiquity through different civilizations is now in vogue again.

Indigo (Indigofera sp.), safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), woad (Isatis tinctoria), madder (Rubia tinctorum), logwood (Haematoxylon campechianum), turmeric (Curcuma longa), saffron (Croccus sativus), henna (Lawsonia inermis), annatto (Bixa orellana), marigold (Tagetes patula) and other plants are covered in the workshops. All these plants are known to work without surprises or failures. They give good results and allow for a basic learning devoid of complications.

Reviewing the literature related to Spanish Ethnobotany that I have been able to consult—from the 12th century book on agriculture of Ibn al-'Awwan, the Arab agriculturist from Seville, to the recent works on the subject—I created a database with more than 300 records of species of flowering plants which at some time or place have been used for dyeing in Spain. For the time being I have not included gymnosperms, ferns or lichens, but these would merit a separate study.

The plants in this database can be conveniently grouped by geographical origin:

A. Plants that are native to Spain, or have been introduced in so remote times that for all purposes can be considered native. This group comprises 130 species frequently cited in Spanish ethnobotany. Their dyeing properties are known since antiquity. Some examples are:

| Genista scorpius (scorpion broom) | ||

|

||

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

| Berberis vulgaris (barberry) | Ligustrum vulgare (common privet) |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

| Rubus ulmifolius (blackberry) | Hedera helix (ivy) |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

B. Plants that have been introduced in a more recent past and have been cultivated for food, ornamental or dyeing purposes. This group comprises, for example all the plants that have been brought to Spain from the Americas since the 15th century, as well as plants that have been brought by the Carthaginians, Romans, and Moors during their respective passages through Spain. Examples from this group are:

| Agave americana (maguey) | Zea mais (corn) |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

| Punica granatum (pomegranate) | Eucalyptus globulus (blue gum) |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

In my twin roles of professional botanist and amateur dyer, I have experimented with every plant—native or imported—that I feel has some dyeing potential. I never work with plants which are protected or in danger of extinction. For my experiments I always use pure wool of xisqueta sheep, a race from the Spanish Pyrenees that has been recovered when it was on the verge of disappearing. This wool has fine and very resistant fibres, well suited for experimenting with new and unknown colorants. For mordants, I use alum and cream of tartar; I use acetic acid, ammonia or washing soda as assists when necessary.

I must admit that many times, after hours of work, the result is a total failure. The flowers or leaves of the plant that I'm testing have a beautiful color and the wool is well prepared, but in the end there is no transference of color to the wool, even after changing pH with the assists. On the other hand, by sheer luck, some humble plant collected from a wasteland or a remote corner of a park—or even bought in some random shop—unexpectedly gives wonderful colors.

Here are some examples of my successes with seeds, peelings, flowers and fruits of urban plants:

|

Maclura pomifera (Osage orange) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar Assist: Ammonia |

||

|

||

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

|

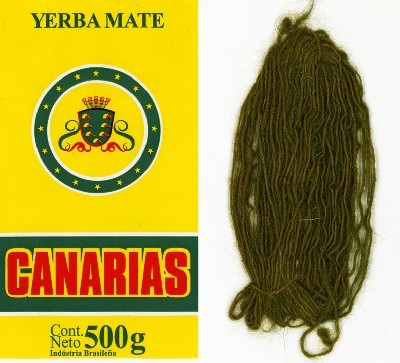

Ilex paraguariensis (hierba mate) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar Assist: Ammonia |

Trigonella foenum graecum (fenugreek) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar Assist: Washing Soda |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

|

Eryobotrya japonica (loquat) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar Assist: Washing Soda |

Papaver rhoeas (poppy) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

|

Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar |

Rosa sp. (rose) Mordant: Alum + Cream of Tartar |

|

|

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Photograph Copyright by T. Sobota and E. Ron

|

Eugenia Ron is a Professor of Botany in the Complutense University of Madrid, now retired. She is still researching Spanish bryophyte flora, but now she has also time to explore the dyeing potential of any kind of vegetal matter that she collects or buys. Eugenia has a website (in Spanish) "El rincón del botánico tintorero": http://www.plantactions.com/rincon, where she writes about her experiments and findings.

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal