A Scottish Colour Kitchen When the summer comes—and it's true that finding two consecutive days of sunshine can sometimes be a little tricky in the West of Scotland—my friend Ruth and I set up our 'Colour Kitchen' in the garden. We invite our friends, most of whom are quilters with a passion for both colour and cloth, to join us for a two-day dyeing workshop. Ruth produces permanent mouth-watering colours using Procion® fibre-reactive dyes and I gather organic materials that yield a beautifully understated palette: together we host a two-day festival of colour. It's industrious, it's messy and it's fabulous fun. My first-ever foray into making natural dyestuffs was a commonplace experience, a regular "beginner's starting point" with papery red and white onion skins collected from the local supermarket, where bemused staff members had bagged them and kept them aside for the weekly visit of the 'onion skin lady'. I could hardly believe the beautiful greens, reds and golds that were gobbled up by the scraps of cotton and silk fabric that were hurriedly pushed into the dye-pot. I was thoroughly hooked.

I quickly moved on to experimenting with the plants, trees and lichens from my garden. Nothing escaped my secateurs: ivy, bracken, eucalyptus leaf and bark (heavenly smells!), blackberries, and every petal of every kind of flower that dared show its face. All this was chopped, soaked and cooked. Even as I was discovering the alchemy of mordants and modifiers, plants beyond my garden began beckoning me to carry them home. My neighbour's garden and the public park burgeoned with possibilities, and I fancied I could hear plants on the distant hills crying "I'm yours, take me!"

Taking from the wild presents one with a difficult situation. UK and European laws give some protection to all wild plants, and Scotland has many of Britain's 150+ specifically protected plants. These include mosses, algae, lichens, and fungi that it is a crime to pick (which prevents seed setting), to damage in any way, or to purposely uproot without the permission of the landowner or occupier. Even plants growing wild are the legal property of somebody, somewhere. So apart from berries and a little wind-blown lichen, I have learned to be content with mainly cultivated plants. Thus, my making of natural dyes is embedded in the rhythms of the year and in tune with the complexities of Scotland's changing climate. It is shaped by all the coming and goings of my own garden, by the gifting of plant material from the gardens of friends, and by my embrace of new shoots, full blooms, fruit, seed and atrophy. I watch for the first flowers, and wait for the last. A final year-end handful of berries will simmer in a saucepan, be strained into a jam-jar and cooled at the kitchen window. Then, when the time is right—perhaps in the grey light of a Scottish winter—the precious 'berry water' will be poured out to flood a length of silk with an extravagant colour that was once hidden in the sun.

My initial documentation of the dyeing process and use of dyestuffs was scratchy, and despite resolutions to do better, it is little improved. Perhaps the colours are stubbornly refusing definition and confinement to my formulae and my notes. To be honest, I enjoy rediscovering what I have sometimes nearly forgotten: what is different this year from last year, and what I cannot truly own, but only borrow—the natural consequence of walks through a Highland glen, of sticks thrown in a dancing stream and the audacious vibrancy of tiny alpine flowers—colour. My favourite piece of documentation is a 5" x 5" pincushion of tiny earthy triangles and squares, teamed with a commercial black: each dyestuff marked with a pearl headed pin and plant name.

For as long as I can remember and for reasons I don't understand, yellow has always been problematic for me—bright yellow (paint, wall-paper, fabric) can make me nauseous and headachy. It is one of life's ironies then, that a colour I love making for textile and quilted work is the yellow that comes from the root of the edible rhubarb plant, Rheum rhaponticum. The dyestuff is best made when the plant is dormant and the root needs dividing—between December and February, and then, only every four or five years—so batches of Rhu-Roo Yellow, as I affectionately call it, are obtained from friends who have the plant in their garden. Rhubarb, with its large poisonous (oxalic acid) leaf blades and bright yellow root, is a multi-purpose plant. Variously medicinal, edible and ornamental, rhubarb, is a traditional Scottish favourite when it's vivid pink/red petiole is sugared and cooked, and served up as a hot sticky crumble-topped pudding with custard or cream! Having first given me food, rhubarb also provides me with mordant from its leaves which are withered in autumn and prepared earlier, outside, while I wear a mask. Marked as poison, they are stored safely outside the house with the liquid disposed of as a poison and the spent leaves on a compost heap. The plant saves its best gift for last, a soft glowing gold from the very root of its being.

I have worked Rhu-Roo Yellow into many textiles pieces: coloured silks and cottons for stitching, and yarns for embroidery and other embellishments. I have paired it with other natural-dye colours, and even with commercially-dyed and printed fabrics. It is a wonder and a yellow I am able to live with, even to love. In my cannon of dyestuffs Rhu-Roo Yellow has a high, secure, and time-honoured place.

By Patricia MacIndoe

Turkey Red Journal

Turkey Red Journal

| Volume 14 Issue 2 | A Journal Dedicated to Natural Dyes | Spring 2009 |

Knit hat dyed with fresh leaf indigo.

Photograph Copyright by Ruth Cadoret

In this Issue

Articles:

• Contact Dyeing

• Earth's Palette: Natural

Colors for Fiber

• How Natural is Natural?

Notes from ISEND 2008

• International Shibori

Symposium 2008

• Returning To Art

• Book Review:

Judith H. Hofenk de

Graaff, The Colourful

Past: Origins, Chemistry

and Identification of

Natural Dyestuffs

Nature's Gallery:

• Diana Maher and

Patricia MacIndoe

Dye samples in the 'Colour Kitchen'

Photograph Copyright by Patricia MacIndoe

Jars of berry water

Photograph Copyright by Patricia MacIndoe

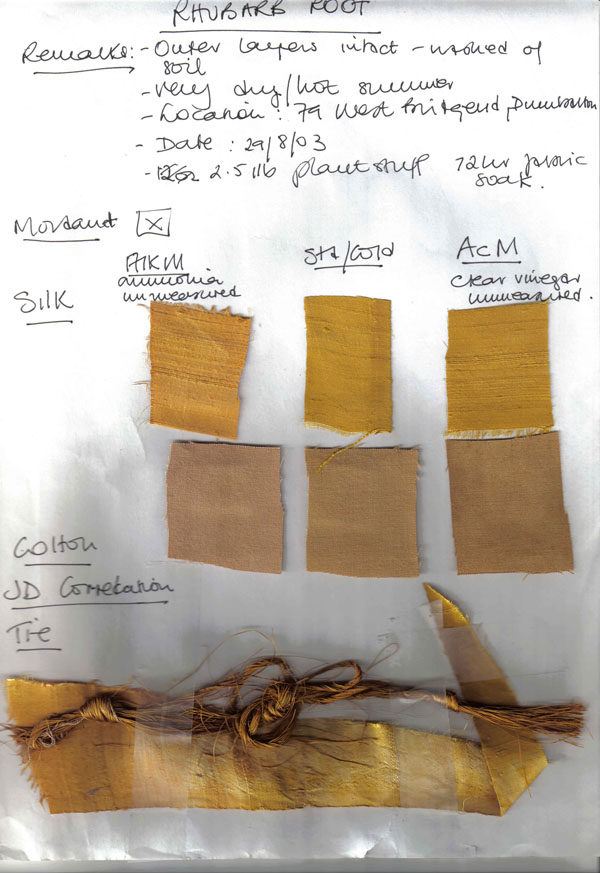

Dye notes

Photograph Copyright by Patricia MacIndoe

Pincushion of dye samples

Photograph Copyright by Patricia MacIndoe

Detail of origami box using rhubarb-dyed fabric

Photograph Copyright by Patricia MacIndoe